It’s been said before that there’s never a dull day in the international diamond industry. After witnessing how 2023 has unfolded so far, I’m sure you’ll agree that it’s an accurate statement.

The industry has seen changes in supply dynamics, an extremely difficult rough market with a significant supply-demand imbalance, bloated polished stocks, the devastating war in Ukraine and the clear expansion and ensuing cannibalisation of the natural diamond space by lab-created products.

We must also consider the economic woes in many consumer markets, and the so-called ‘market disruptors’ attempting to storm the stage.

There are so many factors to consider, and so little time, as the industry seems to be evolving more rapidly than ever.

Against this backdrop, it’s appropriate to ask one question: is the diamond industry in a state of short- term ‘interruption’, or is it facing genuine ‘disruption’?

Diamond market update

|

| Small stones found from Jwaneng pit mine |

Following a sharp and exciting recovery from the doldrums of the market during the COVID-19 pandemic, both 2022 and 2023 have proved to be increasingly difficult markets.

The sanctions which followed the invasion of Ukraine did not lead to the expected blocking of the entire flow of Russian rough into the market.

Somewhat ironically, removing 30 per cent of the global supply might have helped strengthen the market, albeit temporarily.

Despite attempts by the US to stem the flow of Russian rough, the market found new ways to pay for it and direct the diamonds to the wheels in Surat and elsewhere.

The trade became increasingly anxious about excessive polished stocks impacting middle-market liquidity, which in turn weakened rough demand and prices. Most diamantaires had already written off 2022 and hoped to see improvements later in 2023.

And yet the major suppliers were forced to drop their prices, and while contractual obligations allowed De Beers to sell, the middle market experienced little demand for diamonds.

The exception was in the smaller and cheaper ($US100 per carat and below) rough diamonds to keep the Indian factories operational. Smaller producers and tender houses witnessed a decline in prices achieved.

This trend continued throughout the first half of 2023. Polished buyers could see the market weakening and were in no rush to place orders due to their accurate anticipation of further price decreases.

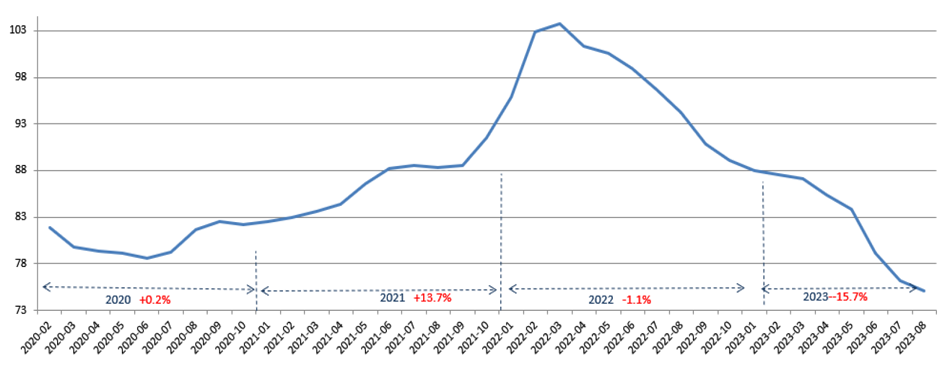

Polished prices have evolved significantly over the past few years and this year alone we have seen an average decline of more than 15 per cent.

If anything, what we witnessed during the first half of 2023 was a market looking for pockets of demand and opportunities to trade or manufacture at profit. At the very least, the intention for manufacturers is to keep the wheels turning at around 60 per cent of full capacity for now. The truth of the matter is that natural rough diamond production is too high compared to what the market can readily absorb.

With that in mind, the entire impact on the natural diamond trade by the introduction of lab-created diamonds is still not entirely understood or quantified.

Where do we go from here?

So, against the backdrop of this fragile situation, what needs to happen to improve the market dynamics?

Reduced rough levels: The major suppliers could reduce production and hold back on sales which would allow a certain ‘rebalancing’ of the middle market.

Although this would allow the smaller producers to sell more or for better prices, the majors still account for 70 per cent of the global rough supply.

Holding back significant volumes would allow prices to stabilise and support the market in the short term.

Practical embargo on Alrosa: Russia’s largest diamond mining company has become ‘caught up’ in a war that has nothing to do with diamonds specifically.

Previous attempts to stem the flow of Russian goods to the factories of India have failed; however, successfully stemming this rough would temporarily support the market due to supply shortages.

At present Russian rough is flowing to the cutting centres and despite the current market and prices being forced downwards, there are reports that around 70 per cent of ‘normal’ volume is currently being sold - principally to India.

The Kimberley Process statistics indicate that Russia is still selling diamonds strongly, with 2022 exports of 36.7 million carats valued at $US3.87 billion ($AU5.8 billion).

The end of the Ukraine war: The diamond market traditionally rebounds on major positive global news.

Should the Ukraine war cease, an emotional rebound globally is on the cards which could mean a surge in diamond acquisition. This would help by reducing the overhang of polished stuck in the cutting centres.

Improved macroeconomic factors: The two key consumer markets of the US and China need to improve economically.

Despite some positives, such as the Nasdaq having a stellar first half this year, there are many negative tailwinds, such as concerns over productivity and very high credit card spending in the US or the deteriorating economic fundamentals, such as deflation and an increase in youth unemployment in China.

Factors such as these indicate potentially weaker short-term consumer confidence and negativity for future diamond acquisition by the mass markets.

It must be said that, right now, none of the above scenarios appears likely to happen. As a result, the diamond market will - in my opinion - continue to struggle for the remainder of the year.

The biggest news of the year

From an outsider's perspective, the partnership between De Beers and Botswana appeared to be crumbling after more than 50 years of collaboration. The media coverage and political rhetoric from certain quarters hinted at a potential collapse of the partnership.

Of course, the stakes were too high for that. Negotiations require a certain back-and-forth, and with Botswana's general election looming in 2024, discussions took on an extra layer of complexity.

Diamonds were discovered in Botswana in 1967 and this discovery has been behind, what I believe is justifiably referred to as, one of the most extraordinary stories of economic development.

To think that all that has been accomplished during the 54 years of agreement between De Beers and Botswana has been centred around a non-essential luxury item! That said, diamonds are just too important to Botswana, its economy, and its people to allow the partnership to end – and so a deal was struck.

In addition to the sales and marketing agreement, which deals with the post-mining distribution of the rough production for the next 10 years, there is the crucial mining licence. This allows Debswana to continue mining its Botswana assets for the next 25 years and requires De Beers to invest billions in underground expansion.

The entire details are not fully public yet. In fact, I hear that some of the final agreements are not signed as some of the finer details still need to be ironed out.

Indeed, in its 1 July press release De Beers indicated that the agreements had been made “in principle”.

These public statements were well received by the industry as a collective; however, we must always remember that the devil will be in the final details.

Certain elements of the deal have been released publicly:

- 10-year sales and marketing agreement until 2033

- 25-year extension of the current Debswana mining licences until 2054

- Increased allocation of diamonds produced by Debswana to the state-owned Okavango Diamond Company (ODC) to 30 per cent with immediate effect

- Further increase of allocation to 50 per cent before the end of the 10-year agreement

- Opportunity to partner on the polished upside in value from exceptional rough valued at over$US500,000

- Creation of the Diamonds for Development Fund which De Beers will fund to the tune of around $US750 million

- Botswana will have some share of exploration success by De Beers elsewhere in the world

|

| Small stones from Jwaneng pit mine |

My reflection on the deal, as we know it to be, is that De Beers had no choice but to accept the demands of Botswana’s government.

The ratchet effect of each successive contract negotiation means that Botswanan governments will now have even greater control of the diamonds discovered in the country. De Beers consequently has fewer diamonds for its client base, both internationally and locally in Botswana.

This reduction will impact the clients in Botswana that receive diamond allocations for local factories. Originally Botswana wanted these factories to be established and supported with allocations from De Beers.

The increased responsibility that ODC will now have in managing the optimal distribution of its higher levels of rough (up to $US2 billion per annum by 2033) is an interesting and important note.

I wonder how many more of these sales and marketing contracts we will ever see?

In any negotiation, there is only so far one side can push before the other party sees no more value in continuing. One must always be careful what they wish for!

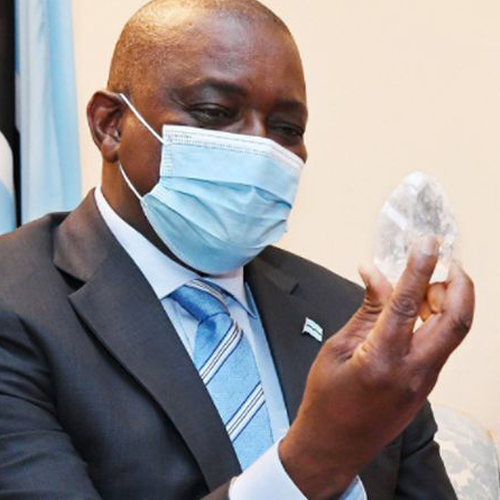

As an interesting aside, as news breaks of more mega rocks being unearthed at Lucara’s Karowe mine, I find myself pondering what ever happened to the stunning 1098-carat diamond discovered at the Jwaneng mine in 2021.

|

| Meaning 'a place of small stones', the Jwaneng open pit mine in Botswana is majority-owned by the Government of Botswana and produced 10,319 kct between Q1 and Q3 in 2022. |

| |

Blink and you’ll miss it

To understand the significance of lab-created diamonds, it’s important to first review the chronology that brings us to the present situation. Over the past two decades, the landscape for lab-created diamonds has altered dramatically.

Improved production methods and economies of scale have meant that production levels have increased dramatically. What was once considered a long-term, distant threat to natural diamonds evolved in the early 2000s into a competitive proposition to the consumer.

In 2017, Swarovski officially launched its lab-created diamond brand Diama in the US.

In a move to counter the threat of lab-created diamonds – and confusing consumers and damaging the natural diamond trade in the process - De Beers shocked the industry at JCK 2018 by launching its Lightbox brand.

The diamond trade embraced the sudden ‘legitimisation’ of the lab-created category and many middle-market stakeholders struggling with wafer-thin margins started developing their own lab-created diamond businesses.

In 2020, De Beers opened a new $US94 million lab-created diamond production facility in Oregon (US). Around the same time, ‘lower level’ brands began moving to lab-created diamonds as consumer awareness increased.

In 2021, Pandora announced that it would no longer sell jewellery with natural diamonds and instead use lab-created diamonds in its new brand, Pandora Brilliance. Retailers also increasingly adjusted store space to incorporate lab-created diamonds.

Lightbox subsequently evolved its customer offering - introducing grading reports and the ‘Finest’ collection, however, the company stayed away from bridal jewellery. It wasn’t long before the US became the key market for lab-created diamond jewellery at the consumer level.

At the same time, trade prices began to decline significantly, dropping to 98 or 99 per cent below ‘Rap’. In February of this year, the Indian government announced a $US30 million five-year research grant to support the indigenisation of lab-created production in India.

The lab-created market is reported to have expanded to approximately $US10 billion in retail sales, around 10 per cent of the entire global diamond trade - and is increasing. However, it is important to realise that the percentage is far higher when you look at actual carats or 'pieces'.

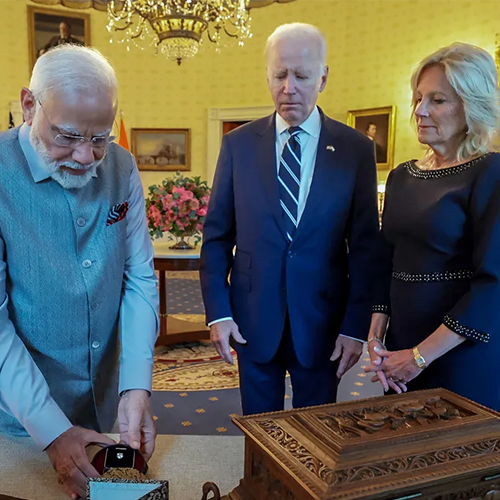

In June of this year, Lightbox introduced its first ‘bridal’ jewellery with a range of 16 engagement rings priced up to $US5,000. Around the same time, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi presented a 7.5-carat lab-created diamond to US First Lady Jill Biden on a visit to the White House.

|

|  |

| One of the world's largest diamonds was been unearthed in Botswana. The 1,098-carat diamond, believed to be the third largest gemstone-quality diamond ever found, was discovered at the Jwaneng mine, around 75 miles from the country's capital, Gaborone. |

|  |

| Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi presented a gift to the US First Lady Jill Biden in Washington during his ongoing state visit - a 7.5-carat lab-created diamond manufactured in a Surat factory in Gujarat. |

|

Higher-end brands had previously resisted any entrance into the lab-created market, except for a few examples such as Tag-Heuer’s Carrera Plasma watch range.

The US lab-created market increased rapidly. Greater margins for retailers lead them to promote lab-created ahead of natural. Some reports suggest that as much as 50 per cent of all engagement rings in the US are now using lab-created diamonds.

What’s known as ‘hybrid diamond jewellery’ also started to appear – pieces that feature both natural and lab-created stones.

What’s next?

As it stands, I believe we are in a specific phase where lab-created products have not found their long-term market positioning. The production of one-carat polished stones is now 2:1 in favour of lab-created, and this number could easily increase.

So, I do not agree with those who claim that the lab-created category is not cannibalising natural diamond sales. The fact is, some consumers are opting for larger lab-created diamonds at the expense of natural diamond sales.

How would you describe such an occurrence, without also describing market cannibalisation?

Even Lightbox has moved to bridal to capture some of this movement. There is an argument to be made that lab-created diamonds are creating incremental demand, which ironically, has been the holy grail for the natural industry for so long.

Trade prices for lab-created rough and polished have decreased significantly and have little room to decline further.

Producers are reportedly struggling, which means that certain businesses will fall away and only those who have sufficient scale and efficiency will survive.

While prices have decreased significantly around production, otherwise known as the ‘upstream’, they have not declined to the same degree for retailers.

This currently leaves a healthy and interesting margin for retailers, and many are enjoying the moment.

At some point in the near future, the ‘cat will be out of the bag’ at the retail level. The combination of competition naturally driving retail prices down along with consumer awareness of the real cost of lab-created diamonds will force retailers to reduce their prices.

Only at this point will the long-term ‘bifurcation’ between natural and lab-created occur.

The recent increase in online commentary around the already low and declining value of lab-created diamonds is, I believe, a sign of this important market movement beginning to happen. The first signs of discounting at the retail level would indicate that this is underway.

With that said, it’s important not to ignore the rise of hybrid jewellery. Who could have expected that?

An important factor that remains unclear to me is the long-term attitude of consumers.

Consumers are being drawn to an alternative product where they can perhaps get a two-carat diamond instead of a 50-pointer for the same money. While many consumers care about the ‘reality’ of diamonds and their origins, many are also unconcerned with the specifics.

Therein lies a large conundrum; the consumer of tomorrow is not guaranteed to act the same as the consumer of today. The next generation may not care if a diamond is lab-created.

Diamonds have always been non-essential luxury items, marketed brilliantly over the decades to represent the ultimate gift of love. The stuff of dreams that is marketed as rare and is perceived as a great store of value.

Now consumers are faced with this rebellious alternative - it looks the same, it feels the same, and yet it is not.

Lightbox was originally not going to enter the all-important bridal market; however, the brand couldn’t resist the opportunity. Today, it’s a direct competitive threat to natural in its biggest segment.

Chart A: Average Polished Index |

| Evolution of polished diamond prices over the past three years. In 2023, there has been a startling decline of more than 15 per cent. |

|

| Source: Compiled by I. Hennig from a number of proprietary and public sources; includes data to August 2023 |

Diamond marketing

The Natural Diamond Council is trying to blaze a trail for diamond and jewellery retailers to follow; however, with a reduced budget due to the loss of Alrosa following the invasion of Ukraine, that has become a greater challenge.

The old ‘Supplier of Choice’ strategy tried to get the sightholders to drive consumer demand; however, from my perspective, this was the wrong approach.

I have always thought that the retailers were well-placed to step in and handle marketing, as they understand the markets and consumers. At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter who does it – so long as someone does!

Tracing and transparency

It has been long suggested that ‘provenance’ is an increasingly important factor supporting the consumer proposition for diamonds.

There are signs that the industry has (incorrectly) elevated the importance of this practice, with the emergence of various blockchain companies.

However, until the average jewellery store customer demands provenance for either natural or lab-created diamonds as a priority, I do not see this issue being the key driver for diamond jewellery sales at the moment

The collapse of Brisbane-based diamond tracing company Everledger – entering liquidation with more than $AU19 million in debt – may support the idea that ‘movement’ around provenance is fleeting rather than permanent.

Indeed, the trade is discussing provenance much more than the consumer. And, regardless, certain well-known loopholes will also need to be closed to make the provenance claim more watertight. And that includes any potentially upcoming attempts to block Russian polished diamonds.

Industry leadership

I have been a part of the diamond industry for 30 years. I have never seen a diamond market facing such a set of complex difficulties simultaneously before.

From my perspective, the industry seems to be suffering from a lack of leadership.

Of course, in the good old (bad old) days De Beers was the custodian - the industry steward – ruling as a dominant monopolistic force. The industry pipeline is no longer so seemingly linear.

However, it still must be said that today - even with a market share somewhere in the 30-40 per cent range - De Beers still does far more for the industry than any other player. No other producer comes anywhere close.

It must be remembered that as the various negotiations take place and producers squeeze more and more out of the value equation, it may become untenable financially for De Beers to continue some of its market-based activities.

Indeed, I often wonder how long it will be before De Beers retreats into becoming solely a diamond mining company.

With its new and improved deal and greater standing on the global stage, perhaps the time has come for Botswana to shoulder some more responsibility.

What does the future hold?

I have always been positive about the long-term future of the diamond industry. With that said, the current macroeconomic factors need to improve.

The tension between lab-created and natural diamonds must settle as soon as possible. Furthermore, the huge polished overhang needs to, somehow, be absorbed.

Until both of these factors are resolved, the short to medium-term future prosperity of the natural diamond industry will remain challenged.

Read eMag