The international jewellery industry has been swept into an impassioned and sometimes heated debate, sparked by several bold marketing campaigns championing natural diamonds.

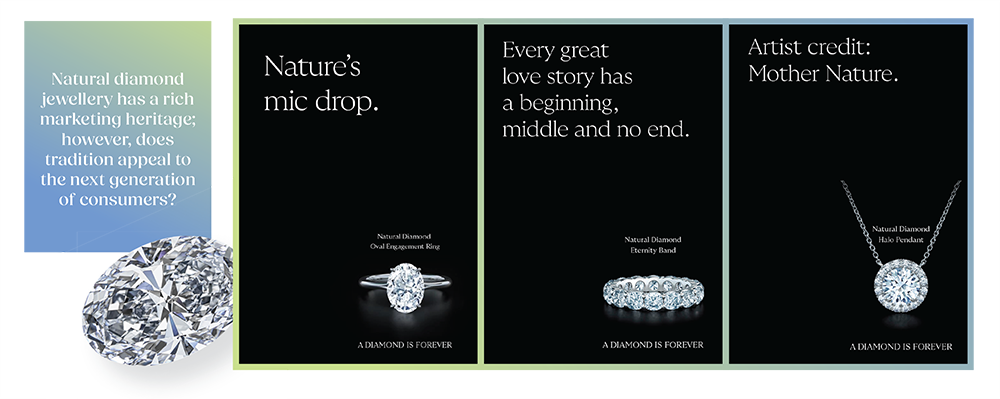

For many years, some supporters of natural diamonds, bound by a shared resistance to the lab-created alternative, have called for more daring and innovative approaches to marketing. he prevailing sentiment was that natural diamonds must meet their challenger with intensity.

It’s an understandable position as the lab-created diamond ‘camp’ has never shied away from confrontation. Advocates have, either rightly or wrongly, disparaged natural diamonds as environmentally destructive products that sponsor conflict and violence in the world’s poorest nations, among other allegations.

In other instances, the lab-created diamond faction has simply suggested that consumers are ‘wasting money’ by purchasing natural diamond jewellery.

These arguments don’t just stem from competing businesses selling lab-created diamonds.

For example, on the eve of Valentine’s Day, the New York Times published a ‘guest essay’ which suggests that conflict-free diamonds are a myth.

“The reality is that there’s still virtually no way of knowing whether a diamond is or isn’t connected to some kind of atrocity,” writes Alex Cauadros, an author specialising in South American social and political commentary.

“The system is riddled with problems: Monitoring is lax, enforcement is nearly nonexistent, and the definitions of “conflict” are so narrow that they exclude the many other forms of violence and abuse that plague the trade.

“Some of the system’s own architects have abandoned it. Without genuine change, consumers may decide that the only ethical stones are those that haven’t been mined at all.”

The decision to publish this article the day before a significant sales event for jewellery retailers drew the ire of natural diamond supporters; however, it’s far from the only stone thrown in this fight.

One week earlier, The Economist published an article with a headline that would send a shiver down the spine of most jewellers: ‘Don’t propose with a diamond.’

“For the past few years, it has been easier to produce a diamond in a factory than to extract one from the ground. This is reflected in price tags,” the article explains.

“At one leading jeweller, $USD5,000 spent on a lab-grown diamond will yield a rock roughly four times bigger than if the money was spent on a natural diamond of similar quality.

“As a consequence, the parsimonious boyfriend now faces an alluring proposition: a larger, nicer diamond; a happier fiancée; and a healthy status symbol to boot.

“Little surprise, then, that the average size of diamonds purchased in America is on the rise, even as the amount of money spent on engagement rings is falling. The world has entered an era of frugal matrimony.”

Similar articles litter the mainstream media, and it must be said that very few can be found that argue in favour of natural diamonds.

With that in mind, it is understandable that the natural diamond camp would argue that it is unjust that only ‘one side’ is allowed to market so boldly.

Why should we always be the ones to take the high road? Don’t consumers deserve to hear both sides?

Consequently, the fear is that lab-created diamonds have captured the hearts and minds of younger consumers with more than just an accessible price point and that a change in strategy is required.

Shaking things up

Over the past few months, the natural diamond camp appears to have finally responded to these mounting calls for a more assertive approach.

The Antwerp World Diamond Centre (AWDC) launched a provocative two-day campaign that playfully challenged consumer perception. A gumball vending machine, placed in a bustling shopping centre, offered lab-created diamonds for a mere five euros ($AUD8.9).

While the campaign was lighthearted, the message was serious. The AWDC emphasised that the stunt wasn’t intended to disparage lab-created diamonds, but to highlight a stark difference between the two categories.

Simply put, no one would dream of filling a vending machine with natural diamonds. CEO Karen Rentmeesters tells Rapaport News that it was a distinction worth highlighting.

“The association that I have, and that I think many people have with things that are in gumball machines, is that it’s not about chewing gum. It’s about cheap goods,” she explains.

“It’s something you definitely wouldn’t hold onto, and you wouldn’t feel bad about losing in a day, and its allure evaporates super quickly. I remember, as a kid, being excited to get something out of the machine, and then it was a huge disappointment. Within minutes, it broke, or I would chuck it away because it was so unimpressive.”

She continued: “I don’t want to seem judgmental of people who buy lab-grown; I just feel consumers need to be informed properly, and price is the first thing that hits you when you do that comparison side by side. We would never put a natural diamond in a gumball machine.”

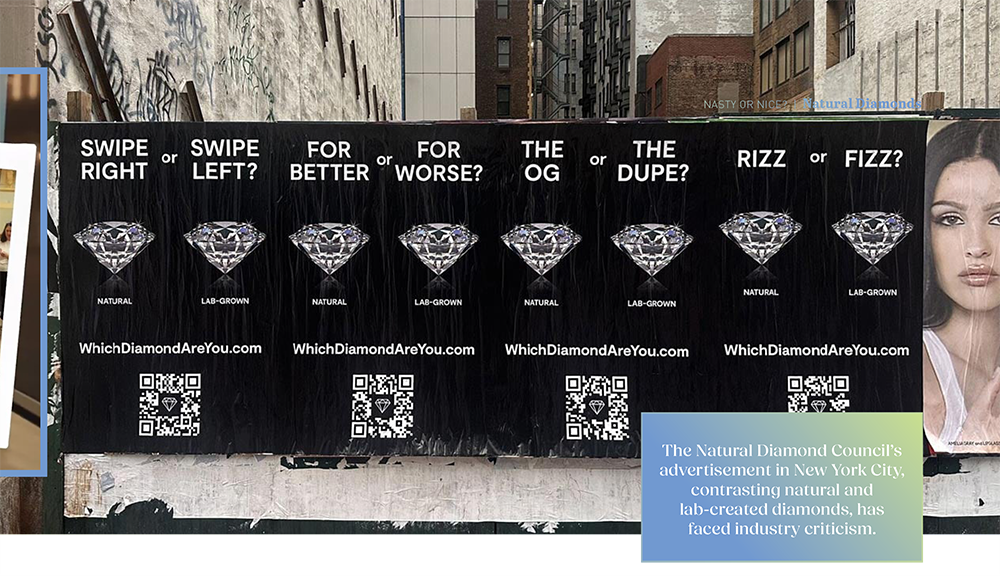

The World Federation of Diamond Bourses launched a social media campaign that dismissed lab-created diamonds as a mere ‘shortcut’ and the Natural Diamond Council (NDC) placed a provocative poster in New York.

In the campaign natural and lab-created diamonds were placed side-by-side with a series of contrasting statements such as “for better vs for worse” and “rizz vs fizz.”

These campaigns have ignited fervent debate across the jewellery industry, revealing deep-seated divisions and provoking broad reflections on the very nature and direction of modern marketing strategy.

Word on the street

Leah Meirovich and Rapaport News have provided fascinating coverage of this ideological clash, with a survey finding that 60 per cent of readers viewed the NDC campaign negatively.

The report suggested that the issue with these campaigns was that they were out of touch with younger consumers.

“Another large reason the marketing doesn’t sit right with younger consumers is because it doesn’t take into account why they buy lab-grown in the first place, those surveyed said,” writes Meirovich.

“When given the options of which factors were most important to them when making a diamond purchase, I offered several choices: Rarity, amount of money spent, value down the road, size, aesthetic, sustainability, traceability and giving back. By far the most popular choices were money spent and aesthetic.

“Consumers wanted something that looked good and didn’t cost a lot. They were more concerned about diverting money to experiences and ‘more important’ purchases like buying a house, vacations and education.”

Industry members contributed to the report, suggesting that the campaign appeared desperate. Critics suggested that ‘mudslinging’ portrays an image of an industry that is out of ideas.

Rob Bates and JCK Online reflected on the history of diamond marketing and the value of branding. It was suggested that natural diamond advocates should focus on emotion, value, and rarity.

Addressing both sides of the debate, Bates emphasised that a healthy dose of reflection was necessary for all parties involved.

“It’s good that the industry is taking marketing seriously. Even the online arguments, as overwrought as they get sometimes, show that people care. We saw that passion in the lab-grown community’s early days. That probably helped it grow. But let me give two pieces of advice,” writes Bates.

“To my friends in the lab-grown world: Congratulations on building an incredible business, almost from scratch. When miners run ‘negative’ ads against you, that’s a sign you’re winning.

“But you shouldn’t root for natural to fail. Not only will that cause human suffering in producer countries — or, to be precise, more suffering — it’s hard to imagine many mom-and-pop retailers maintaining their business on $USD1,000 engagement rings.

“Instead, created [man-made] gem sellers should look at any new natural diamond marketing as an opportunity. During the pandemic, sales of both kinds of diamonds rose in tandem. As long as the two sides don’t get into a nasty tit-for-tat, that could happen again.”

Indeed, the consensus is that lab-created diamonds are here to stay. Natural diamonds must market their unique worth without alienating younger, idealistic, and price-sensitive consumers.

Bates adds: “To my friends in the mined business: Lab-grown diamonds are not the sole cause of the current mess. The NDC was founded in 2015, before the great lab-grown boom, because of fears that diamonds were falling out of favour with millennials.”

“If your business is based on a certain level of advertising, and that advertising ceases, you shouldn’t be surprised when sales fall too - especially when so many lab-grown diamond companies do market their product.

“There’s a reason Coca-Cola and McDonald’s — two brands with close to universal brand awareness — still advertise heavily. In the 1990s, McDonald’s slowed its ad spend; sales plunged 28 per cent.”

Two sides to every great story

It is entirely understandable that many within the industry would call for harmony and fair play. Such appeals to unity are both predictable and, in certain respects, justified.

However, the situation is far more nuanced, touching on the core principles of effective marketing. Chief among them is the fact that it is impossible to please everyone. Some individuals, regardless of their circumstances, will always find something to criticise.

The natural diamond camp is damned if they do and damned if they don’t!

If they remained passive, choosing to ignore the rise of the lab-created alternative, they would likely have been dismissed as complacent or out of touch. However, now that they’ve adopted a bolder stance, a different chorus of critics has emerged — ironically, levelling the very same accusation.

Furthermore, while some may disapprove of the confrontational approach, for others, being aggressive doesn’t mean being dishonest. It could be argued that just because natural diamond marketing has become more direct and bold - even blunt - it doesn’t necessarily lack integrity or credibility.

When devising marketing strategies, it’s essential to recognise a fundamental aspect of human psychology – we are wired to understand ourselves and the world around us through contrast.

By defining opposites, we shape meaning and draw boundaries. We often come to know who we are by discerning who we are not; our preferences are shaped not only by what we choose, but also by what we reject.

Furthermore, storytelling is a cornerstone of compelling marketing, which thrives on tension and contrast. Without conflict, there is no narrative; without differentiation, no clarity of message.

Conflict is memorable, and marketing that provokes emotion tends to be more enduring. Natural diamonds have deep emotional capital from which to draw; however, without a source of tension, the material risks falling flat.

Every compelling story needs an antagonist, and introducing an adversary, even implicitly, sharpens the narrative. As legendary filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock once said, “The more successful the villain, the more successful the picture.”

Additionally, modern consumers don’t simply purchase products. They adopt the personalities that those products represent. It has been said that, ”People don’t drive cars; they wear them.”

In a competitive market, messages of neutrality and universal appeal often fade into the background. Consumers are drawn to distinction and to narratives that resonate with who they are and who they aspire to be.

Consequently, businesses that dare to draw clear lines and stand for something, not everything, tend to thrive.

Settle it in the street

Without a point of difference, even the most storied product can lose its relevance.

Portraying your competitor as the adversary is not always morally neat and can feel tribal, because it is.

Marketing isn’t a moral endeavour; it’s a commercial discipline, intended to promote clarity, resonance, and conversion. The final objective is increased sales.

With that said, there are many examples of successful marketing strategies that have relied on confrontation with a competitor. Perhaps the most famous is the Cola Wars, the long-standing competition between The Coca-Cola Company and PepsiCo.

These two companies have engaged in mutually targeted marketing campaigns promoting the direct comparison of products for decades. The most iconic example is the ‘Pepsi Challenge’, which began in 1975.

The campaign is centred around a blind taste test in shopping centres and other public locations, where consumers are presented with two blank cups – one containing Pepsi and the other Coca-Cola.

Consumers are encouraged to taste both drinks and vote for their preferredone. The results are presented, and the audience is informed that, on average, consumers prefer Pepsi to Coca-Cola.

The format of the challenge has been presented in various forms over the years; however, the core principle remains the same. An article published by Glemont Consulting, a US-based marketing firm, suggests that the ‘Pepsi Taste Test’ reshaped industry standards.

“This ground-breaking campaign’s influence was not limited to the immediate boost in Pepsi’s market share. It established new norms for competitive advertising and reshaped the way businesses viewed their brand’s relationship with consumers,” the article explains.

“The enduring legacy of the Pepsi Challenge remains etched in marketing strategies, serving as a testament to the power of innovation and consumer-centric advertising.

“The Pepsi Challenge played a vital role in redefining the norms of competitive advertising. Directly comparing one’s product with a competitor’s in a public platform was considered risky and even unorthodox before this campaign.

“However, the success of the Pepsi Challenge demonstrated that this high-risk strategy could pay off, encouraging other brands to adopt similar tactics in their advertising campaigns.”

Smartphones & Vehicles: Defying convention

The Cola Wars are far from the only example of confrontational marketing between competing brands in modern business. As another example, consider the advertising ‘conflict’ between BlackBerry and Apple.

The late 2000s marked a transformative era in mobile phone design, as the industry began to shift away from keyboards and keypads, embracing the simplicity of touchscreens.

During this period, BlackBerry dominated the smartphone market and was often described as both a ‘corporate necessity’ and an unlikely cultural icon among teenagers.

The landscape was changing with the introduction of Apple’s iPhone. The minimalist design, smooth user experience, and touchscreen interface redefined the standard for smartphones and threatened BlackBerry’s dominance.

BlackBerry released an audacious advertising campaign, directly challenging Apple. In a clash of fruits, a small blackberry hurtles towards an apple, splitting it in half.

After a dramatic pause, the text reads: “The world’s first touch-screen BlackBerry. Nothing can touch it.”

Apple responded by flipping the script, with an advertisement showing an apple shattering a blackberry. The camera lingers on the screen before closing with text that reads: “Simple facts.”

It was a subtle suggestion that Apple was invincible and that there would be no challengers in the smartphone market.

While it could undoubtedly be described as an assertive and aggressive response, it would prove accurate.

Another lesser-known, but arguably even more impressive example of comparative and confrontation marketing was released by German automotive manufacturer Audi.

It may be the most uncomplicated and inexpensive advert ever created by a car company; however, it was powerful. The television commercial begins with a message: “What do you want in a car?”

Four keys are displayed with attributes of rival car manufacturers: ‘Design’ for Alfa Romeo, ‘Comfort’ for Mercedes-Benz, ‘Safety’ for Volvo, and ‘Sportiness’ for BMW.

The four rings, holding keys from the competing brands, are transformed into the interlocking rings of the Audi logo.

The final text reads: “In one car only?”

It’s a fascinating and memorable example that seems to break traditional conventions not only of identifying competing brands but also of praising them.

Does this attitude look good on me?

It’s clear from these examples that confrontational and comparative marketing, when executed clearly, can improve product visibility and consumer engagement.

These examples prove that a strategic rivalry in advertising can capture attention, provoke conversation and engagement, and improve resonance with consumers.

With that in mind, it would seem justified for natural diamond advocates to believe that remaining relevant by defining the category in opposition to an alternative may not just be helpful, but essential.

Almost all marketing strategies have some form of risk - ask Bud Light if they had their time over, would they use Dylan Mulvaney again?

Today’s younger consumers are supposedly increasingly media literate, and some may view polarising messaging as manipulative and insincere.

Industry analyst Avi Krawitz, writing for The Diamond Press, states that the diamond industry needs to enhance its understanding of the preferences of younger consumers.

“The days when a single slogan could reshape culture are behind us. Today’s consumer is fragmented, values-driven, and often sceptical,” he writes.

“Tradition and permanence still matter — but they’re filtered through a lens of identity, ethics, and emotional resonance. Consumers connect most with brands and stories that reflect those values.

“The good news? The diamond industry has those stories in abundance. De Beers and the NDC can help amplify them — but they can’t do it alone, and it’s not just a matter of funding.”

Krawitz suggests that retailers and suppliers need to work closely with the De Beers Group to reshape the diamond industry at the point of sale, specifically, by emphasising education in interactions with consumers.

“The uncomfortable truth is that category marketing is not a silver bullet,” he continues.

“It can spark curiosity, reinforce value, and boost perception, but it won’t convert today’s consumer without immersive retail experiences, authentic storytelling, and digital engagement that meets people where they are

“The belief that a single message — and messenger — can ‘save’ the market is more nostalgic than strategic.”

If the natural diamond camp adopts an aggressive stance, it risks being perceived as defensive, bitter, and insecure. These are qualities that conflict with the category’s aspiration to be seen as timeless and unchallenged.

Weighing in on the diamond marketing debate, industry analyst Edahn Golan says that it is impossible to create the perception of ‘exclusivity’ as a luxury product if you disparage a competitor.

“The goal of category marketing is to advance diamonds and increase sales, not to badmouth the competition and risk alienating consumers,” Golan writes.

“Assuming that the diamond industry wants to increase sales by positioning natural diamonds as a coveted luxury item, there are plenty of notable examples of such marketing by Cartier, Tiffany, and many others. None of these campaigns have included slamming the competition. And the competition in the luxury goods market is fierce.”

“Instead, these brands speak of themselves and what they have to offer. Note Cartier’s frequent use of icy cool nature scenes and panthers that emphasise their red brand, or Patek, and its hinting at generational wealth with the slogan: You never actually own a Patek Philippe. You merely look after it for the next generation.”

There’s a common belief in business that naming your competitor affords them legitimacy and visibility, potentially provoking consumers to consider options they might not have otherwise.

A study published by the Harvard Business Review suggested that praising, and not disparaging, competitors was effective with modern consumers. This is particularly interesting given the success of the aforementioned Audi advert.

“We also found that consumers who were most sceptical about advertising in general exhibited the greatest increase in positivity about a brand when it praised its competitors,” the 2022 report explains.

“This is likely because these consumers tend to have less positive baseline feelings towards brands, and so when they witness a brand demonstrate warmth by praising a competitor, it makes a more substantial impact on their impression of the brand.

“Ultimately, there are no one-size-fits-all solutions, and every organisation will have to determine the approach that will be most effective — and feel most authentic — for its unique brand and customers.”

The report concludes: “But our research suggests that praising the competition can substantially benefit brands, both in terms of consumers’ perceptions and bottom-line sales. Plus, in a world that’s increasingly cynical and rife with conflict, it couldn’t hurt for brands to add a small bit of positivity to the mix.”

Finally, once a business defines itself in opposition to a competitor, there is the risk of becoming strategically ‘trapped’. The narrative switches from autonomy to reaction, tethering your identity to the actions of your rival. You have forfeited the tempo!

With all that said, it is challenging to fault the natural diamond camp for choosing to confront lab-created diamonds directly. While the category has historically relied on tradition and prestige, these values alone appear increasingly insufficient to secure loyalty in a price-sensitive market.

Positioning natural diamonds in contrast to the lab-created diamond alternative – even when the products are chemically identical – helps reinforce their distinct value and is a step towards maintaining relevance in an evolving market.

Same-same but different

Although the two products are chemically identical, positioning natural diamonds in contrast to lab-created diamonds emphasises that they are not the same.

Any parent of identical twins will testify to that - each is different even though they are identical!

It could be argued that this is the very heart of the debate. With that in mind, how about this for an idea?

An advertising campaign that uses identical twins to explore the subtle yet powerful differences between natural and lab-created diamonds.

The twins appear the same; however, their personalities are worlds apart. One twin is grounded and introspective, shaped by experience and time, representing a quiet strength.

The other twin is bold, polished and larger-than-life; however, they lack depth. Through a series of scenes, these personalities are reflected. For example, one twin is insistent on preserving a beloved family tradition, while the other is disinterested and easily distracted.

The contrasts are never moral judgments — just reflections of depth, personality, and origin. The campaign doesn’t need to preach or disparage; it only needs to provoke reflection and encourage consumers to consider that, while some things may look the same on the surface, they are, in fact, different.

The natural diamond industry is at a crossroads. In a market where lab-created diamonds appear to be winning on price and perception, silence may no longer be a strategy. Bold comparative marketing can clarify value and distinction.

Conflict may be uncomfortable; however, contrast creates meaning, and rather than retreat, natural diamonds can reframe the narrative. ‘Shaming’ the alternative doesn’t need to be the mission; however, drawing a line in the sand is critical.

Aggressive comparative campaigns won’t please everyone, but they don’t have to. Great brands don’t whisper; they stand for something.

READ EMAG