Legendary mathematician, physicist, astronomer, and alchemist Sir Isaac Newton once famously wrote, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”

As a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment, Newton employed the metaphor to describe his work as building upon the foundation laid by others. It’s an acknowledgement that progress is often incremental and relies on the contributions of previous thinkers and researchers.

This sentiment is popular among the ‘unsung heroes’ of the jewellery industry, gemmologists. Behind the scenes, these researchers play a critical role in an industry that, at the surface level, is driven by beauty.

Over the past three years, Jeweller and the Gemological Association of Australia have published a series of articles dedicated to the giants responsible for constructing gemmology.

Despite common misconceptions, gemmology is far from a modern invention. Humans have adorned themselves with gemstones and used them as symbols of status since the dawn of civilisation. However, the scientific study of gemstones has its roots dating back at least to the 19th century.

Structured education in gemmology began to take shape in the early 20th century.

Notably, the Gemmological Association of Great Britain was established in 1908, followed by the launch of the Gemmological Institute of America in 1931, offering the first formal courses in the field.

Since then, gemmological education has expanded globally, with institutions such as the Gemmological Association of Australia (est. 1945) contributing to the training of skilled professionals who form the backbone of the jewellery industry today.

Gemmologists are essential to upholding the integrity and authenticity of the gemstone and jewellery industry. Through extensive training and hands-on experience, they develop the expertise necessary to identify and evaluate gemstones accurately.

This work provides the assurance jewellers need to sell — and consumers to buy — with confidence. And so, with that said, let’s wind back the clock.

|

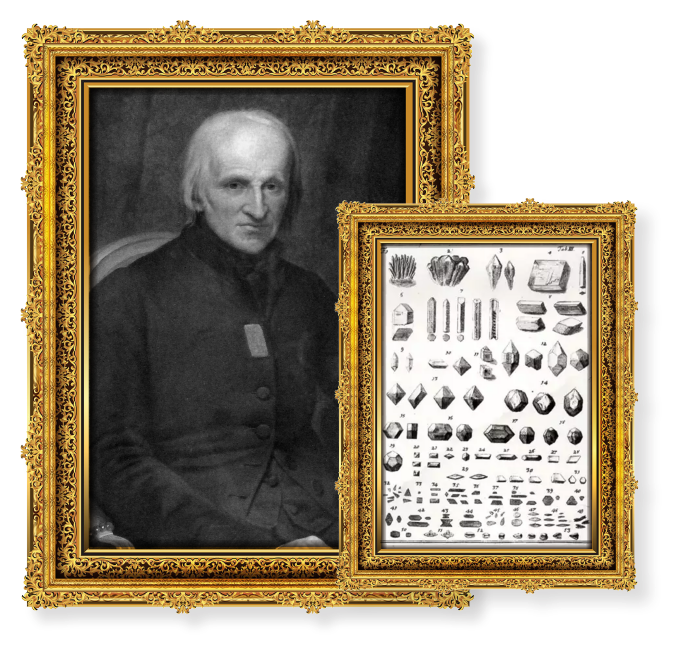

| René-Just Haüy |

René-Just Haüy, well-known as the founding father of crystallography, was a French priest and mineralogist.

In one version of a famous tale, a critical moment behind the discovery of crystalline structure occurred when Haüy accidentally dropped a calcite crystal onto the floor, shattering it.

Examining the fragments of calcite, he noted it “had a single fracture along one of the edges of the base. I tried to divide it in other directions and I succeeded, after several attempts, in extracting its rhomboid nucleus”. Haüy discovered ‘cleavage’.

By continuing to break calcite into smaller pieces and observing the same step-like feature, he concluded it had the same internal structure regardless of its size.

Before Haüy’s research, understanding of crystal structure was limited to external morphology.

An example of this is the crucial contribution Nicolas Steno made with his observation that for a particular mineral, the angles between corresponding faces of a crystal are constant.

Reading of his contributions to the field of crystallography, some may think Haüy’s work to be detached from gemmological practice today.

However, as any good gemmologist would know, it is this understanding of a crystal’s internal structure that allows us to separate one gemstone from another.

Haüy’s ground-breaking study opened the door for researchers to recognise cleavage and planes of weakness, to predict in which directions a gemstone may appear different colours (pleochroism), or to understand how light may interact with a gemstone, to name a few of the properties dependent on crystal structure.

|

| George Frederick Kunz |

George Frederick Kunz was a renowned American mineralogist. His humble upbringing led to his education in public schools. Kunz did not graduate with a degree and instead channelled his hunger for knowledge and passion for minerals into self-teaching.

Through his ventures exploring the geology of nearby regions and exchanging specimens with overseas dealers, Kunz had amassed a collection of more than 4,000 mineral specimens by the time he was still a teenager.

At the age of 23, Kunz secured a position at Tiffany and Company as a gemstone expert before advancing to vice president. This was the first example of a jewellery retailer having a gemmologist on staff.

During his years at Tiffany, where he worked until he died in 1932, Kunz travelled the world, gaining experience with mineral and gemstone localities.

During his extensive travels, a pink variety of the mineral spodumene was discovered in San Diego County, California, between 1902 and 1903. This new pink gemstone was named ‘kunzite’.

Shortly after this discovery, a known gemstone mineral was found to occur in a previously unknown attractive pink hue – beryl.

Kunz named the new variety ‘morganite’ in honour of his friend and financier, JP Morgan. Morgan was a lifelong supporter of the arts and sciences.

Kunz produced hundreds of articles on minerals and precious gemstones in his time, as well as well-known titles such as Gems and Precious Stones of North America, The Curious Lore of Precious Stones, The Book of the Pearl: Its History, Art, Science and Industry, and more.

|

| Eduard Josef Gubelin |

Like so many prominent gemmologists, Eduard Josef Gübelin was an inquisitive child. Born into a watchmaking family, his father, Eduard Gübelin Sr., was the owner of a store.

As an artist who specialised in fine watches, Gübelin’s father demanded a high standard in their practice. In 1923, Gübelin’s brother opened a small gemmological laboratory.

With a newly opened jewellery atelier, Gübelin wanted to ensure the legitimacy of all gemstones handled by their craftsmen. This modest gemmological operation laid the foundation for the renowned Gübelin Gem Lab, which recently celebrated its 100th anniversary.

In 1940, Gübelin published his first work on gemstone inclusions – an article on distinguishing Burma and Siam rubies in Gems & Gemology. His proposed classifications of inclusions were further developed in later publications and are now widely adopted in the gemmology field.

During his lifetime, Gübelin documented the inclusions of tens of thousands of mineral and gemstone specimens.

He also created the very first desk-model gemmological spectroscope, co-founded the International Gemmological Conference and the International Colored Stone Association (ICA).

Where Gübelin stood apart from many other gemmologists was his appreciation for inclusions. He dedicated his work to a feature of gemstones previously regarded as an unwanted blemish, and in doing so, changed the science of gemmology.

Understanding inclusions plays a role not only in mineral identification but also in distinguishing between natural and synthetic gemstones, as well as determining a specific gemstone’s country of origin.

Gübelin knew this better than anyone.

|

| Richard T. Liddicoat Jr. |

Richard T. Liddicoat’s father was a professor of engineering at the University of Michigan. His grandfathers worked as copper miners.

In 1940, Liddicoat joined the Gemmological Institute of America in Los Angeles as assistant director of education. Robert Shipley had established the GIA just nine years earlier, and with its rapid expansion, needed support in leading its educational direction.

While teaching gemmology and developing courses, Liddicoat also worked on producing the Handbook of Gem Identification, the first book of its kind designed to assist students through their studies and aid the practising gemmologist.

In 1952, Liddicoat was named Shipley’s successor and accepted the position of executive director of GIA. During this time, the industry faced a dilemma with standardising diamond grading.

In collaboration with colleagues across Los Angeles and New York, Liddicoat developed the iconic ‘4Cs’ system by which diamonds are routinely graded worldwide today.

This new system enabled diamond dealers and retailers to communicate with each other and their consumers in the same language, minimising discrepancies and allowing diamonds to be categorised on a uniform basis.

By the 1960s, Liddicoat oversaw training some of America’s largest jewellery retail teams. Around the same time, he travelled to Japan to gather information and develop a course on cultured pearls, which also led to the development of the first GIA pearl grading system.

Liddicoat was also an avid supporter of innovation on the technology front. He contributed to and developed several gemmological instruments in his time. These include the Diamolite, the Proportion Scope, and the prism spectroscope.

In honour of his 40-year dedication to serving the gemmological and jewellery industries, the National Museum of Natural History in Washington DC named a gemstone species of tourmaline after Liddicoat in 1977 -‘Liddicoatite’.

|

| William Hanneman |

William (Bill) Hanneman, known by many as Dr. Bill, was a monumental and inventive figure in the world of gemmology. He worked as a research analytical chemist for the DuPont Research lab, the Standard Oil/Chevron Refinery, and the Kaiser Center for Technology.

Gemmology was introduced to Hanneman by his father, a gemstone cutter, and remained a life long passion. He became concerned about the cost of pursuing a formal diploma and set out to make gemmology more widely accessible.

He tackled this issue with practical solutions, including designing and producing the Hanneman Gemmological Instruments, which included the polariscope and dichroscope pocket kits, as well as a range of gemstone filter kits.

Based on their composition, structure, and impurities, gemstones absorb, reflect, and transmit light in different ways. Filters enhance these differences, making them easier to observe.

The Hanneman instruments were made as cost-effectively as possible, keeping prices down and making them affordable for anyone interested in gemology.

His background in chemistry offered a unique and insightful perspective on the subject. Hanneman developed his diamond cut grading system to simplify the evaluation of diamond cuts.

He called this system the Hanneman Diamond Cut Grading System, and it remains available for free at the International Gem Society and Canadian Institute of Gemology.

Hanneman’s vast knowledge of gemmology and his contributions to the field make his position as a ‘self-ordained gemmologist’ quite extraordinary. Despite this unofficial credential, his dedication and knowledge of the subject were internationally recognised.

Donald B. Hoover worked for a long time with the United States Geological Survey as a senior scientist specialising in seismology, volcanology, geothermal energy, and nuclear waste disposal.

After he retired from USGS in the 1980s, he delved further into gemmology. He was known for his energy and enthusiasm, particularly regarding geological and gemmological discovery and research. Hoover was also a member of the editorial review board of The Australian Gemmologist.

|

| Richard T. Liddicoat Jr. created the iconic ‘4 CS’ system to standardise diamond grading, focusing on cut, colour, clarity, and carat weight and improve industry communication. |

One of Hoover’s notable contributions is his work on the thermal properties of gemstones. Thermal inertia is a measure of how quickly the surface temperature of a material can be changed with the application of heat.

It depends on the material’s thermal conductivity, specific heat, and density. A material with high thermal inertia will resist changes in temperature and feel cold to the touch. In contrast, a material with low thermal inertia will easily change temperature.

Hoover compiled a comprehensive table that arranged materials based on their thermal inertia. This work has been instrumental in gemstone analysis, providing a valuable parameter for accurate quantitative probes.

Hoover also made significant strides in the study of fluorescence in gemstones. Fluorescence is the emission of visible light by a gemstone material when exposed to radiation of shorter wavelengths, such as ultraviolet light.

Hoover’s research, published in a paper entitled ‘Fluorescence excitation-emission spectra of chromium-containing gems,’ explained the effectiveness of the crossed filter method in examining emission spectra in gemstones such as rubies.

This study has been pivotal in understanding how fluorescence can be used as a gemmological tool. His research has not only advanced our understanding of gemstones but also provided practical tools and methodologies for gemstone identification. His work continues to be referenced in contemporary studies, underscoring its enduring relevance.

Australia – The Lucky Country

Australia is often referred to as the ‘lucky country’ – a phrase that originated as a critique, but has evolved to a point of national pride. It was coined to highlight the nation’s prosperity as a product of circumstance rather than innovation. It is now used to celebrate the land’s natural abundance.

Beneath the vast landscapes lie treasures of remarkable beauty: enchanting pearls from the outback, lustrous pearls from the northern waters, and sparkling diamonds from the remote wilderness.

This natural bounty has not only enriched Australia’s cultural and economic identity but also cemented its role as a key contributor to the global field of gemmology.

Australian men and women have made significant contributions to our modern understanding of diamonds and gemstones, elevating the science and appreciation of gemmology on the global stage.

|

| Thomas Hodge-Smith |

Thomas Hodge-Smith was a pioneering figure in the fields of mineralogy, gemmology and the earth sciences in Australia. Born in 1894 in England, his family immigrated to Australia when he was two years old.

After a military career, Hodge-Smith resumed work at the Mining Museum before leaving in 1919 to work for the Australian Museum, being promoted in 1921 to mineralogist.

During his early years at the museum, he conducted extensive fieldwork, particularly on the occurrence of zeolite minerals in New South Wales and mica in Central Australia.

He went on to discover a new mineral at Broken Hill, which he named ‘sturtite’ after Australian explorer Charles Sturt. He is documented as having a ‘chief love’ for crystal measurement and drawing, reflecting the enthusiasm for crystallography he shared with his sister.

He had a passion for meteorites, a topic he would research until his death.

Hodge-Smith had an interest in the study of gemmology and was, in part, responsible for introducing the first courses to Australia. He was the tutor for the gemmology course ran by the Federated Retail Jewellers Association.

His contributions to gemmology are reflected in records from 1946 from The Australian Museum: “He was also very interested in gemmology and was unremitting in his efforts to instil into all concerned with the jewellery trade a strong regard for the scientific aspects of their calling.”

Between 1935 and 1941, he served as editor for the Australian National Research Council’s publication, Australian Science Abstracts. From 1925 until his death, he was a teacher of mineralogy at Sydney Technical College.

In 1943, Sandy Tombs became one of the first people in Australia to complete a gemmology course. He was one of the three founders of the Gemmological Association of Australia and its first chairman.

Sandy’s legacy lived on when his son Geoffrey took up the gemmology baton and became a Fellow of the GAA.

|

| WC Taylors 103 King Street Sydney |

For more than five decades (1950s-1990s), Geoffrey Tombs served the field of gemmology in Australia. His first paper in The Australian Gemmologist, published in 1958, documented synthetic diamonds observed through the microscope.

Tombs went on to publish more than 30 articles in the GAA’s flagship journal.

The investigative work continued to guide jewellers and gemmologists. An example is ‘Fakes and Frauds – Caveat Emptor’, which encourages caution when soldering is completed on a jewellery piece containing yellow sapphires.

The sapphire changed colour and became ‘as near to a cape colour diamond as may be’.

Another example was his 1991 paper ‘Some comparisons between Kenyan, Australian and Sri Lankan Sapphires’, where he strongly advised against heating a sapphire in a setting. If the sapphire was from Kenya, it may turn green!

Tombs founded the Valuers Association of Australia and designed a jewellery valuation form for retailers with his colleague Kenneth Mansergh.

The duo advised that the purpose of the valuation had to be stipulated, whether for insurance purposes, retail replacement, or other purposes.

These forms became standard practice in the industry and helped reduce the use of jewellery valuations as a marketing tool, rather than for their intended purpose.

His reputation as a gemmologist, with a thorough knowledge of gemstones and their treatments, was respected both nationally and internationally.

In his honour, the Geoffrey Tombs Research Fund was established in 2004 with an initial grant from the GAA Federal Council and continuing contributions from the GAA-endorsed Gem Studies Laboratory.

|

| William Hicks |

William H. Hicks, known to most as Bill, was a gemmologist who, after completing his studies with the Gemmological Association of Australia, dedicated over a decade of his life to developing The Australian Gemmologist.

His professional background in the publishing industry, as a part of the third-generation publishing firm Hicks Smith & Son, made him an incredible asset to the editorial team.

He was appointed editor of the publication in August 1981 by the Melbourne-based committee.

Hicks worked diligently over the next 12 years, editing and rewriting papers by hand and preparing layouts.

This was no small feat in an era before computer processing, when documents were rewritten and edited on a typewriter.

In 1982, Hicks introduced selected colour printing throughout the publication as visual aids to support relevant articles.

Previously, colour printing had been reserved solely for the cover.

Hicks was dedicated to improving the journal while also being pragmatic about reducing the rising costs of publishing a comprehensive, high-quality journal.

Under his guidance, by 1983, The Australian Gemmologist reported readership across 30 countries.

His dedication to the journal was made possible by his wife, Rose Hicks, who assisted as secretary. The couple loved to travel, though they never let this get in the way of publishing the journal. Accounts of Hicks preparing the journal for publishing from Athens and Florence is a testament to his unwavering dedication to the publication.

|

| William Hicks had an unwavering dedication to the Australian Gemmologist |

Through his role as editor and involvement with the GAA, he formed many friendships in the field of gemmology, including Richard Hughes and Eduard Gübelin, whom he met during his travels.

In 1991, the GAA made Hicks an honorary life member in recognition of his significant contribution to the association and The Australian Gemmologist. After his death, the W.H. Hicks Prize was founded in his honour.

Grahame Brown was a practising dentist until his passing, and alongside this profession, he achieved a great deal in the field of gemmology. He was a prolific writer and researcher, and by the end of his life, he had published more than 500 gemmological papers.

Brown’s extensive role as editor of The Australian Gemmologist is detailed on the GAA website.

“Prior to 1982, a general committee was responsible for the production of the journal without the specific role of an Editor,” it reads.

“Dr Grahame Brown followed on in the esteemed footsteps of Bill Hicks and was Editor from

1994 until his death in January 2008, the longest tenure to date.”

He was awarded the first Research Diploma of the GAA for his investigations into the structure and properties of precious corals. His Summer 1991 Gems & Gemology article on treated Andamooka matrix opal remains the subject’s definitive work.

He also wrote ground-breaking articles on various kinds of ivory - perhaps an apt topic for a dentist!

He not only contributed through his writing and research, but was also an accomplished editor. In 2001, Brown was appointed editor of The NCJV Valuer, Australia’s dedicated journal for the evaluation of gemstones and jewellery.

He was a contributing editor to the fifth edition of Robert Webster’s Gems: Their Sources, Descriptions and Identification, first published in 1994. It is a reference book used by gemmological organisations across the world.

|

| Jack Stanley Taylor Gemstone Collection |

Born in August of 1910 in Greenwich, Jack Stanley Taylor was one of the founders of the Gemmological Association of Australia and is referred to as the ‘father of Australian lapidary.’

He joined the family business after finishing school, as all the Taylor children did. Here, he started his jewellery apprenticeship directly under his father and grandfather.

By the 1940s, Taylor had fallen in love with gemstones more than jewellery and started to drift away from the retail side of the industry. He enrolled in a gemmology course offered by the Federated Retail Jewellers Association.

This was taught by the Curator of Minerals at the Australian Museum, Thomas Hodge-Smith.

Shortly after graduating, the FRJA ceased offering their courses, and Taylor and other students believed they had identified a gap in the market.

Australia needed more formal education opportunities in gemmology.

With the desire to educate the industry, gemstone enthusiasts, and consumers, three colleagues joined forces and proposed the foundation of the GAA.

The GAA’s inaugural meeting was held on 29 October 1945 in Sydney. Sandy Tombs was elected chairman, and Taylor was elected secretary. George Osborne accepted the office of patron, and David Mellor took that of president.

In just five years, the association had created divisions in Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, and Western Australia. In October 1947, Taylor sat his exams and completed the first diploma in gemmology. He was the first to earn the post nominals FGAA (Fellow of the Gemmological Association of Australia).

Throughout his life, Taylor travelled around Australia, fossicking and operating his successful lapidary business.

Today, a sample of his extensive gemstone collection can be seen in the Australian Museum in Sydney and the NSW division of the GAA.

Corinne Sutherland’s passion and dedication to gemmology helped shape many educational pathways that the industry benefits from today.

She graduated from the University of Melbourne with a degree in science. She then began working in research and development for food used to aid troops serving overseas in World War II.

Sutherland developed an interest in gemstones and, in the 1950s, applied to the GAA’s Victorian Division to complete her Diploma in Gemmology.

At the time, this was no small venture, as study at the GAA was reserved solely for people within the gemstone and jewellery trade. Sutherland challenged this tradition by persuading the GAA that education in gemmology should be open to all.

Successful at this task, she was the first non-trade person to complete the Diploma Course. Due to her tenacious nature, education in gemmology studies through the GAA is available to both ‘trade’ and ‘non-trade’ people.

Sutherland proved adept in gemmology, graduating with her diploma in 1960 and winning the Lustre Prize for the highest practical results in Australia.

She was fascinated by and loved diamonds, and was instrumental in establishing the Diploma in Diamond Technology course.

The Sutherland Prize, established at the GAA in 1971, was awarded to the student who achieved the highest marks in the Diamond Technology course.

Due to her immense contribution to the organisation, Sutherland was made an Honorary Life Member of the GAA in 1980.

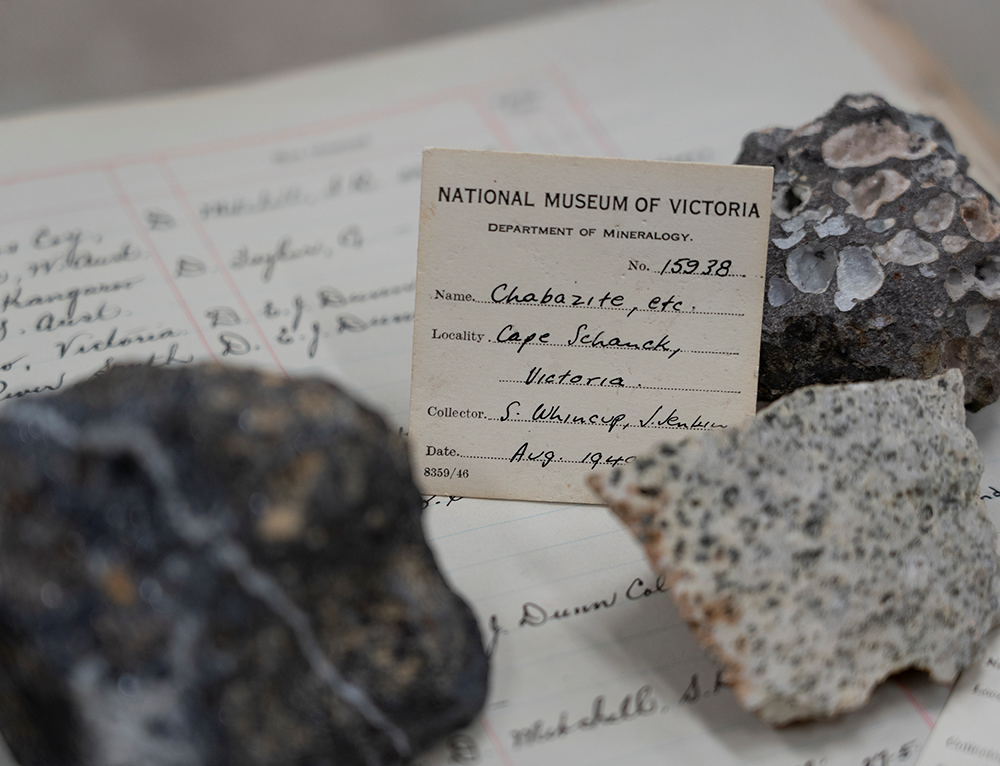

Sylvia Whincup was a pioneering female figure in the fields of earth sciences and gemmology in Australia. She graduated from Melbourne University in 1942 with a Bachelor of Science degree in geology and chemistry and completed her Master of Science in 1943.

She was married to Charles Reginald Whincup, a Royal Australian Air Force flight officer who died while serving in World War II. Whincup gave birth to their son, Peter Reginald Whincup, in 1944, the same year she published her master’s thesis.

In 1946, Whincup was appointed a mineralogist at the National Museum in Melbourne.

Museums Victoria notes that she was the first person appointed to this official post and was tasked with reorganising and registering the museum’s mineral and rock collection.

Her appointment received media coverage due to her specialised skillset and, in part, her success as a woman in such an important role.

A feature article about Whincup, ‘Rocks Are Her Livelihood,’ was printed in The Argus in July 1947. It describes her position at the museum as a “most remarkable job for a woman”.

Whincup expanded the museum’s collections by sourcing mineral specimens and encouraging her colleagues to do the same. In an article written for Museums Victoria, Nik McGrath and Robert French reflected on the contribution made during her time at the museum.

The authors noted that Sylvia added more than 5,000 specimens to the collection, including 167 new species — an increase of more than 30 per cent in just four years.

She was a pioneer during a time when it was difficult for women to progress professionally. She navigated personal tragedy and motherhood while trailblazing a career in the earth sciences.

|

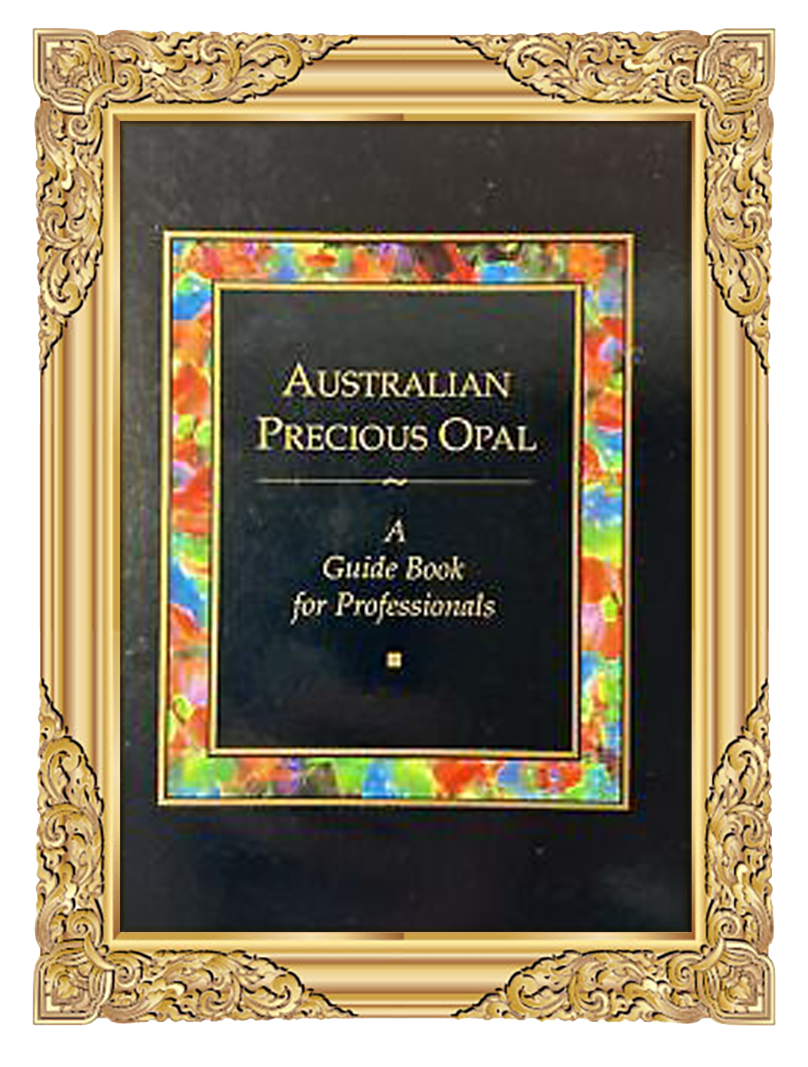

| Andrew Cody's first book is an essential resource |

Andrew Cody had an unrivalled passion for Australian opals and dedicated most of his life to promoting and celebrating this unique gemstone. His love for collecting gemstones and minerals began at an early age, and a school excursion to Coober Pedy further fueled his passion for opals.

In 1964, his interests turned to cutting opal, and he went on to complete studies in Valuations at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology. His passion and understanding of the market provided the foundation for his business, Cody Opal, which he founded at the age of 20 in 1971.

In 1991, Cody wrote the book ‘Australian Precious Opal — A Guide Book for Professionals’. It was published in English and Japanese and remains an essential resource for industry professionals and gemmologists alike.

Cody was involved in championing the declaration of opal as Australia’s national gemstone, which became official in 1993.

In 2000, Cody co-founded The National Opal Collection, which has its head office in Melbourne and showrooms in Melbourne and Sydney. The business includes museum displays, retail sales, and wholesale exports to the international gemstone industry. It is now recognised around the world as the primary source of opal.

In 2010, Cody and his brother Damien published a second book, ‘The Opal Story,’ which was translated into six languages. In 2018, he produced a limited release of sixty opal master sets.

Each set contains 216 opal samples from deposits worldwide to assist with identifying, classifying, and grading opal.

Many of the individuals detailed thus far have overcome war, violence, and personal tragedy, driven by a passion for education, science, and gemstones.

While the impact of conflict is frequently noted during the lives of those living in the early 20th century, it has also impacted modern research. Campbell Bridges was a world-renowned geologist, gemmologist, dealer, and prospector who made a tremendous impact.

|

| Campbell Bridges |

His childhood in South Africa and his father’s work exposed Bridges to various gemstones, which he began to collect. He worked across South Africa and Zimbabwe before expanding his explorations into Tanzania, where he made many critical gemmological discoveries.

In 1967, Bridges discovered deposits of ‘tsavorite’, a green variety of grossular garnet, in the mountain ranges of northeast Tanzania. The discovery was made in the Taita Hills, near the Tsavo National Park, which inspired the gemstone’s name.

Along with the discovery of tsavorite, Bridges became enamoured with a purplish-blue stone he encountered at local markets. He purchased rough of the purplish-blue stone and sent it to New York for further testing.

The gemstone caught the attention of key figures in the industry, including Tiffany & Company jewellers, prompting Bridges to bring tanzanite to the global market. He did this for several years until the government nationalised mining.

Bridges was a founding member of the International Coloured Gemstone Association. He also owned the Scorpion Mine in southeast Kenya.

Despite living in Kenya for more than 40 years, the success of his tsavorite mine made him a target for a large, organised crime syndicate. Bridges had received numerous threats, prompting him to alert police and hire a security staff.

Tragically, despite these efforts, his life came to an end when he was ambushed by a gang of more than 30 armed men. The incident devastated the gemmology community and was a confronting reminder of the volatile and dangerous conditions that can exist in the industry.

|

| Sylvia Whincup - National Museum of Victoria Collection |

The story continues with you!

This list is by no means exhaustive, and Jeweller and the GAA welcome any and all suggestions for future profiles. The stories of these pioneering figures in gemmology reveal far more than scientific achievement – they reflect the resilience, passion, and steadfast commitment to uncovering truth in a field that is as complex as it is beautiful.

Many of these people faced formidable obstacles: the chaos and devastation of war, the absence of formal education, and even rigid social structures that outright excluded women from scientific fields.

Undeterred, these individuals carved out their place in history with innovation, perseverance, and an unshakeable belief in the value of their work. These contributions laid the groundwork for much of what we may take for granted today.

Indeed, jewellers, suppliers, retailers, researchers, and consumers all rely on the principles and practices shaped by these trailblazers. It’s a reminder that behind every diamond and gemstone lies not only a geological wonder, but also the human spirit of discovery.

READ EMAG