Where will the diamond industry be in 12 months? Given the intricate and ever-changing dynamics of the market, it's an increasingly difficult question to answer.

In April, news broke that mining behemoth BHP Group Limited had set its sights on Anglo American for a potential takeover. While not unprecedented, this development could reshape the landscape of the mining and diamond industries.

The board of Anglo American has since unanimously rejected three bids, suggesting they undervalue the company.

Rival parties such as Glencore and Rio Tinto have been predicted to enter the fray with their offers. When these bids occur, there are always many different moving parts and other potentially interested parties also tend to surface. So far, no other party has made a public move.

A third bid valued at around $USD49 billion was tabled on the deadline. This bid was also immediately rejected. However, Anglo American agreed to extend the deadline by another week and is now discussing potential terms.

The latest twist before publication is that Anglo-American refused to extend talks further, and BHP confirmed it would not make a formal bid. It seems the takeover attempt has collapsed - for now.

What happens next between BHP Group and Anglo American remains to be seen. BHP is principally interested in copper assets in Chile and Peru and not in the South African iron ore or platinum assets.

South Africa faces challenges with a troubled economy, rampant unemployment, political strife, and elections are days away. Anglo American has been the backbone of the South African corporate world for more than a century.

De Beers, as the owner of the Venetia mine in the Limpopo Province in South Africa - among other mines in its portfolio located elsewhere — is also directly involved in the mix.

BHP exited the diamond industry willingly in 2012 when it sold its 80 per cent share of the Ekati mine in Canada, which accounted for 6 per cent of global diamond supply, for $USD500 million. A decision was made at the time to focus on larger, longer-life assets.

It is, therefore, difficult to imagine BHP retaining the world’s most important diamond producer, which the company has indicated would be subject to a strategic review following a possible takeover. Right now; however, nothing is certain.

Ironically, De Beers has among the best long-life diamond assets in production volumes, reserves, and position on the cost curve.

These would typically be seen as a prized asset; however, it is complicated by producer government shareholdings, declining profit arrangements with its local partners, and increasing beneficiation pressures.

Meanwhile Anglo American has announced that, as part of its standalone strategy, it will slash its portfolio to focus on copper, iron ore and polyhalite (a form of potash) and confirmed that, among others, De Beers will be either sold or spun off to unlock value.

So, regardless of what happens to Anglo American, the next phase in De Beers's fabled history is about to unfold.

And so this immediately begs the question: what will happen to De Beers?

Most observers seem to think De Beers will be sold. Will it be spun separately and listed? Will another company acquire De Beers?

De Beers would like to push for an IPO and keep control of its destiny. An announcement of a new De Beers strategy is now slated for JCK.

There have already been many interesting suggestions. These include acquisition by the Botswana government, which is a 15 per cent owner of De Beers and 50 per cent owner of Debswana.

Botswana is arguably the stakeholder with the most to lose or gain. This will be a critical piece of the next stage of the story.

President Masisi said Botswana does not want a hostile owner of De Beers and wants Anglo American to separate quickly. Other mining companies, as well as Gulf sovereign wealth funds and luxury companies, have also been mooted as possible suitors.

The Botswana government has been eager to diversify from its significant reliance on diamonds; however, it may feel compelled to invest in protecting its future.

Diamonds have been increasingly volatile in recent years, so only a committed player will have a reason to make a move. Many would see an independent or new benevolent owner of De Beers as a positive for the diamond industry juggernaut.

At this point, nothing is inevitable; however, it’s a development that has shaken the diamond industry. It is undoubtedly the hottest topic of conversation in the cutting centres as the industry waits for further news.

Who would have imagined De Beers potentially becoming a ‘transactional orphan’ in a battle between major mining companies? And yet, that is what is on the cards here.

There are strong rumours that Anglo American has already spoken with potential buyers about an exchange of De Beers’ assets.

|

De Beers

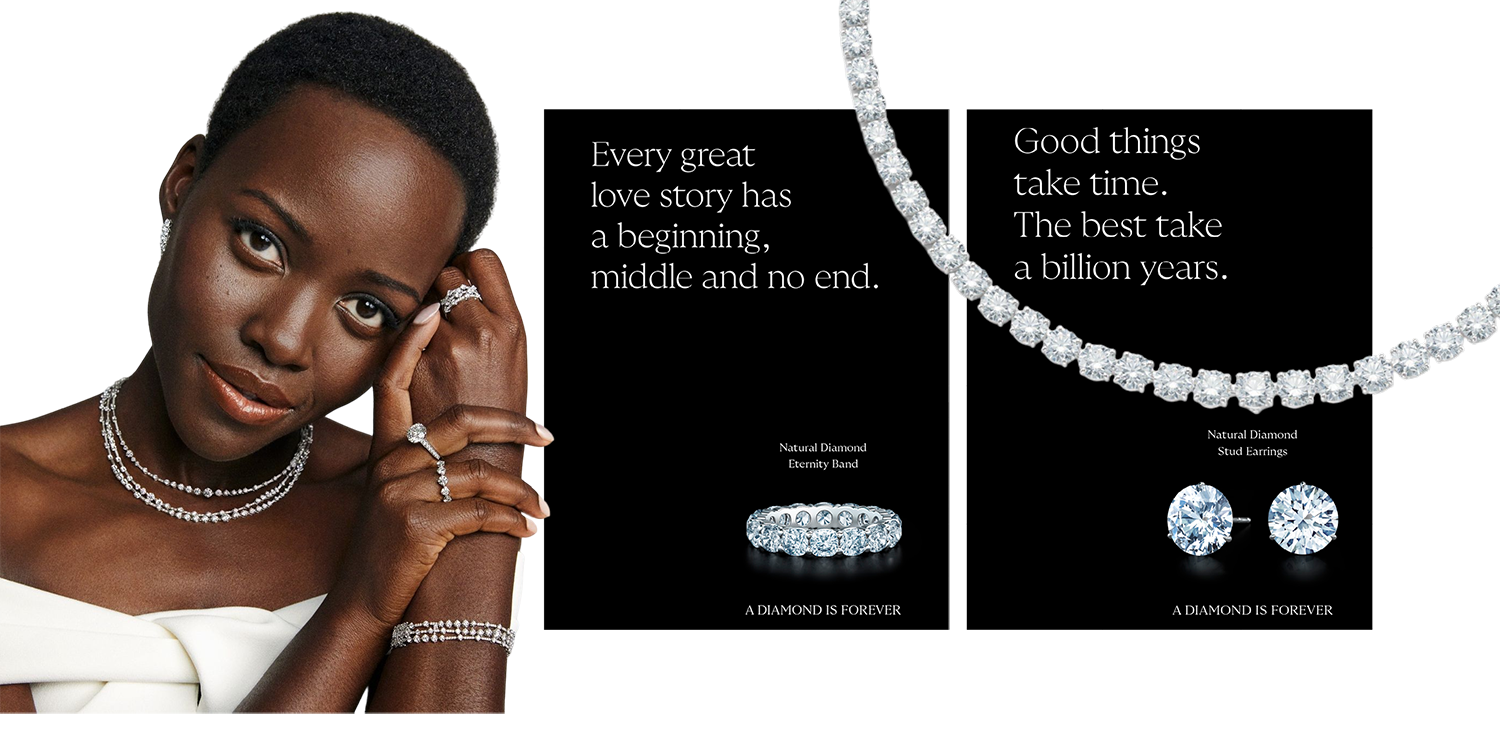

L to R: Ambassador Lupita Nyong'o; 2023 Marketing campaign; Tennis necklace |

|

Timing is everything

It must be said that this news comes at an inopportune time for the diamond trade.

In the past, when I was asked what I expected from the diamond market in the first half of this year, I said that I thought “stability would be a success”.

The sudden potential change in ownership or structure of De Beers is not exactly what I would call industry stability!

The past year was terrible for the rough diamond market. Many issues of late have badly buffeted it, and sentiment is extremely cautious.

The following were key developments:

- Oversupply of rough: There was simply too much rough available on the market, more than the trade required.

- Decline in demand: A decrease in natural polished demand was caused by global macro-economics.

- Rivals gaining momentum: The increased production and marketing of lab-created diamonds has generated a significant consumer uptake.

- This is particularly true in the US, which is by far the world’s largest diamond jewellery market. This has created a gaping hole in the natural diamond industry.

- Falling rough prices: This was a natural effect of the oversupply and stagnant polished situation.

- Decreasing polished prices: Bloated polished stocks encouraged discounting in the competitive polished environment.

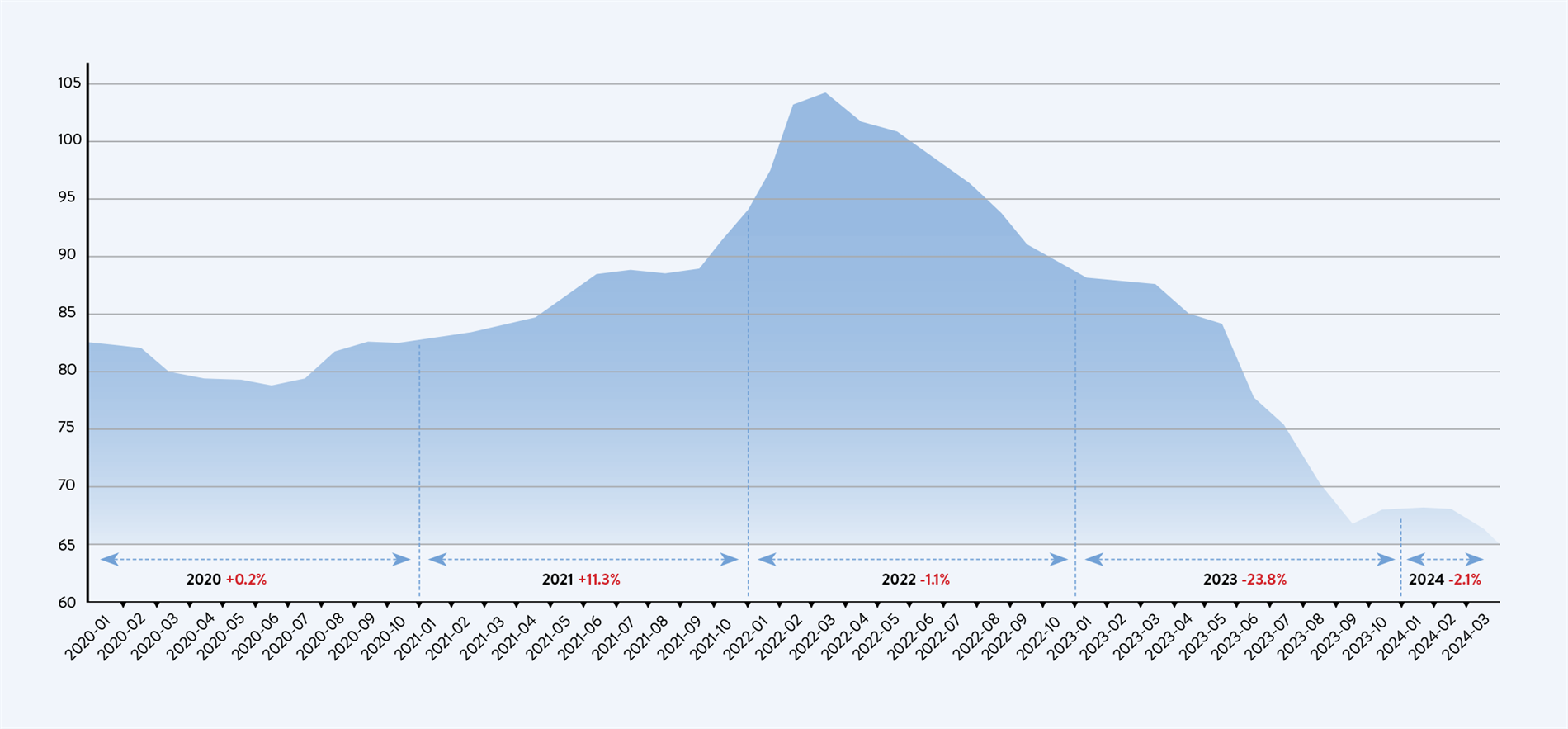

- The chart from I. Hennig, the diamond broker, shows the average polished diamond price index has decreased by around a one-third in the past two years.

- China’s changing priorities: An important market for polished diamonds, China, has seen demand decrease due to a shift in consumer interest in gold jewellery.

- India’s import ban: An informal two-month rough import ban until mid-December gave India’s polishing industry breathing space. This was the third time this had occurred in 15 years.

- Rough market paralysis: The two-month rough import ban forced all producers and suppliers – both large and small – to cease selling rough until ‘better times’ in 2024.

The above developments understandably impacted mining companies' results. De Beers announced a sizable decrease in annual sales, from $USD6 billion to $USD3.6 billion.

Profitability decreased from $USD1.41 billion to $USD72 million, followed by $USD100 million in cost-cutting and a reduction in budgeted 2024 production from 29-32 million to 26-29 million carats.

While this unfolded, Russian diamond producer Alrosa announced a 9.2 per cent increase in turnover, as well as a 15 per cent decrease in profit to $USD925 million.

This included its first shareholder dividend in two years.

|

Natural Diamond Council

L to R: Ambassadors Ana De Armas and Lily James; Cicada necklace |

|

Rough diamond import ban

The rough diamond ban in India is significant and should be put into context.

This is the third such ban in recent memory. The first was during the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09, and the second was during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is an unofficial trade-led strategy to block rough imports, which signals the upstream to temporarily cease supplying rough.

This acts as a ‘pressure release’ for India’s trade by removing the excessive build-up of rough in manufacturing centres and decreasing the pressure to purchase rough. It is a short-term, immediate fix.

However, it also holds the rough upstream in the hands of the miners, suppliers such as Okavango Diamond, and also the secondary trading market.

An added consequence is that this strategy creates liquidity in the middle market due to the lack of purchasing, which leads to a renewed demand for goods once the ban is concluded.

This is a logical strategy; however, there is one fundamental long-term problem. Unless rough production is aligned with demand, the market will experience continued stagnation. This phenomenon may be a coincidence or a sign of a fundamental imbalance in the industry.

The market recovered quickly after the Global Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic - within six months. No one expects a dramatic improvement this time.

Even by conservative estimates, over-production is 25 per cent higher than the current demand for polished diamonds.

If the market does not improve in demand for polished diamonds, it is only logical that the more marginal mines should be placed on care and maintenance or sold.

This subject is not often discussed, but it is poignant. Rough prices are currently very low, and not all mines are operating at a profit. Diamond mining assets, for those who may be in acquisition mode, are inexpensive right now.

CHART 1: AVERAGE POLISHED INDEX |

|

| Chart 1 shows the average polished diamond price from January 2020 onwards. Bloated polished diamond stocks lead to discounting in a competitive market, and this chart demonstrates the significant fall in prices over the past two years. This data was compiled by Hennig and Co Ltd from a number of proprietary and public sources. |

|

An impossible problem to fix

Complexity in the diamond industry continues with the ‘Russian issue’ following the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Despite attempts to restrict the flow of proceeds to Russia through various sanctions, diamonds continue to be sold and manufactured, destined for jewellery consumer markets worldwide.

While this has occurred on a smaller scale than we have seen with Russia’s oil and gas industries, all attempts to block Russian diamonds have failed.

That said, the latest moves driven by the G7 have caused significant disruption and consternation in the global diamond trade.

In December, the G7 introduced a new sanctions regime based on technological traceability. The EU adopted these rules and handed Belgium (Antwerp) a leading role in its implementation.

Since 1 January, import restrictions have been in place for non-industrial diamonds mined, processed, or produced in Russia. These apply to diamonds of any size when imported directly or via a third country without transformation.

Under these sanctions, Russia cannot export diamonds directly or indirectly to G7 markets, including the EU. This step did not include rough that was ‘transformed’ in a third-party country to become a polished diamond.

The G7 went a step further on 1 March, introducing indirect import restrictions on all Russian diamonds above one carat – polished or rough. This was intended to be a ‘staggered’ import ban on Russian diamonds from third-party countries.

Importers must now prove that diamonds do not have a Russian origin through documentary evidence during a six-month transition period.

A verification and certification system using traceability technologies monitors compliance with this ‘indirect’ import ban.

The plan is that diamonds could be traced from ‘mine to finger’; theoretically, Russian diamonds would be excluded from this chain. The implementation of the traceability systems is due to be complete by 1 September.

In recent months, it has become clear that this roadmap was utterly unworkable. On 1 March, there were no monitoring systems in place, and the industry moved to a flimsy ‘self-verification process’ — which was not what was intended.

When this plan was announced, it was suggested that these decisions had been made in close consultation with the broader diamond industry. The industry has vehemently disputed this.

Over the past two months, the diamond industry has been up in arms about what’s occurred so far. The industry wrote to the Antwerp World Diamond Council to object to the sanctions.

The letter argued that while the industry applauds the objective of blocking Russian goods and understands the importance of provenance and transparency, the measures implemented will adversely impact the competitiveness of the Antwerp diamond industry.

This contributed to Ari Epstein's recent resignation as CEO of the Antwerp World Diamond Council. Other trade associations have followed suit, registering their disapproval of the new measures.

It’s important to note that these measures only relate to the production of ‘new’ diamonds. They do not apply to previously mined diamonds; significant polished stock sits in consumer markets. Some estimates place this stock at $USD10 billion alone.

Of course, the diamond industry is not localised – it is global – and other diamond centres have rightly expressed frustration at their exclusion from this system.

The sentiment is that these centres were not considered legitimate additional nodes when the diamond verification and certification scheme was designed.

What happens next regarding the ‘Russia issue’ is anyone’s guess — we will have to wait and see. That said, the current plan has glaring issues.

Russian diamonds can simply stay outside of the G7 and continue to be processed. India, Dubai, and China are not members of the G7.

Furthermore, sanctions are broken by parties that relabel Russian diamonds as coming from alternative sources, whether mines or countries. Finally, it must be remembered that Russia is the largest producer of high-quality small diamonds.

While crucial for specific categories, such as the watch sector, these diamonds do not fall under any planned measures and will continue to be used in the G7 markets.

There are reports that the European Union plans to exclude 'grandfathered' goods from its sanctions on Russian diamonds. This means rough diamonds imported from Russia before January 1, 2024, and polished diamonds imported before March 1 — or September 1 for stones under 0.50 carats — will be exempt from the ban. This has not yet been confirmed.

Sanctions targeting Russian diamonds are not likely to end any time soon. The proposed solution is a flawed, unbalanced, and ill-fitting attempt to stop a single problem, creating a new series of issues for an unprepared industry.

There are emerging rumours that the US may reconsider its position on diamond sanctions. The impracticality of the current approach may have become apparent to certain lawmakers and politicians. This potential shift in strategy could mark a significant change in the global diamond trade landscape.

IN A NUTSHELL

State of the Diamond Industry in 2024

|

|  |  |  |

In January, the rough market stabilised at new levels. The De Beers Group decreased its prices to better align with these new conditions. | Rough sales started to return to relatively healthy levels and the market began to move and absorb rough. | Sales of polished diamonds have improved slightly from 2023. In response, prices have more or less stabilised. | Despite signs that the diamond market has began to recover, industry stakeholders remain cautious due to widespread uncertainty about future developments. |

|

Let’s talk about lab-created diamonds

By now, most people have accepted that lab-created diamonds have eaten into the natural diamond business.

The damage this category has caused is significant and continues to contribute to issues with natural rough demand and prices.

As recently as one year ago, I heard prominent trade members still disagreeing with the assertion that lab-created diamonds were cannibalising the natural diamond trade.

By this, I mean eating into natural diamond sales and altering the image and perception of diamonds among consumers.

As technology has rapidly improved and economies of scale have taken effect, the emergence of larger, better-coloured, and higher-quality lab-created diamonds has accelerated. Today, most polished lab-created stones weigh between .5 and 3 carats.

This directly impacts the 1-5 carat natural diamond market and has been a significant factor in the decline of rough prices.

It must be remembered that lab-created diamonds are polished to the same exacting standards and have all the fire and brilliance of their natural counterparts.

In recent years, lab-created diamonds have strengthened their position in the market and are now prominent in consumers' minds.

Lab-created diamonds now account for almost half of all engagement rings in the US, and there’s little reason to believe this figure won’t increase in the future.

The most significant risk is that this demand shifts further away from natural diamonds at either the retail or luxury level, exacerbating the issue.

Some analysts suggest that these new lab-created diamond consumers will eventually become natural diamond consumers later in life.

While I understand the logic behind this argument, I am not convinced.

Consumers who purchase lab-created diamonds are not guaranteed to ‘shift up’. It’s equally possible they have their ‘diamond needs’ met with an initial lab-created diamond and move on.

With that said, all is not lost. In the trade, lab-created diamond prices have fallen significantly, and you can now buy a G colour VS1 of any size for $USD250 per carat.

Imagine this for a moment – a high-quality two-carat lab-created brilliant round triple ex with no flu – readily available in unlimited quantity for just $USD500.

This price drop has not yet happened fully at the retail level. Consumers are still paying a significant markup for lab-created diamond jewellery.

For the natural diamond market to recover, consumers must make a stark distinction between lab-created and natural diamonds.

With that said, ‘praying’ that lab-created diamond pricing will fall at the retail level and that consumers will develop an understanding of the distinction between the two categories is not enough. Hope is not a strategy!

Natural diamond marketing needs to ‘step up’ in this regard.

If lab-created diamond retail prices continue declining, however, retailers may decide to shift the focus of their business away from lab-created diamonds because there simply isn’t enough money to be made.

Shortly before publication, Lightbox Jewelry announced it was lowering the price of its lab-created stones by around 40 per cent. It has also been announced that Element Six will 'suspend' production of lab-created diamonds for use in jewellery. This is a strong signal to the rest of the industry.

This is a step in the right direction, as it will undoubtedly show the consumer that lab-created products are a less expensive product in a separate category; however, more is needed.

Lab-created diamonds are here to stay; let’s be clear about that. However, they will be at a much lower retail price point.

The category will unavoidably take away a tangible market share from natural diamonds, which, as premium products, still have a position to defend.

The announcement of a marketing campaign between De Beers and Signet promoting natural diamonds to 'Zillenials', especially in the bridal segment, is a welcome new initiative.

The industry started this year in a ‘better mood’ than it finished 2023 with. The rough moratorium had its desired short-term effect.

- The rough market stabilised at new levels in January, with De Beers dropping its prices to align more with the market.

- Sales returned to relatively healthy levels, and the market started to move and absorb rough again.

- Polished sales have been slightly better, and prices have more or less stabilised.

Thinking back to my mantra for the first half of this year – stability would be a success – these developments suggest that the industry has found surer footing.

The industry is now entering the seasonally quiet period, and demand is expected to decrease slightly over the coming months — this is not cause for alarm. Casting aside the issue of BHP and Anglo American and what may happen next, the natural diamond industry needs to fight back.

The industry's leadership must resolve the ‘Russian issue’ to the best of its abilities and position natural diamonds more advantageously against lab-created diamonds. Rebalancing the rough production profile against demand is also required to drive demand.

To achieve these objectives, the industry needs leadership, vision, and positive tailwinds from factors outside of its control. De Beers's importance to the industry in this regard should not be underestimated.

Many people may not agree with De Beers’ approach to the challenge of lab-created diamonds; however, no other company comes close to attempting to lead the diamond industry.

A break-up of De Beers, a possibility that looms over the already struggling diamond industry, would be nothing short of traumatic. The irony of this situation is significant for those who have been around a long time in the business.

Marketing remains critical; however, this expensive strategy requires much effort and time. India and China remain the markets where I see the best opportunity. These markets are still capable of driving additional demand for natural diamonds.

Structural changes in the diamond industry are inevitable. One thing is certain — we need more than just hope.

Read eMag