Shopping centres play an integral role in both the retail sector and the national economy and are a powerful force in consumer behaviour.

In 2022, it was estimated that shopping centres accounted for $183 billion in sales, approximately 8.3 per cent of Australia’s gross domestic product.

The retail sector accounts for around 10 per cent of the Australian workforce, of which two-thirds are employed in shopping centres. Indeed, retail is the single highest private sector contributor to employment in Australia.

Shopping centres are also important to and for jewellery retailers.

They have traditionally provided a steady stream of shoppers and potential customers who roam the aisles; however, these centres also offer other benefits that suit jewellery stores, perhaps a little more than most other retail categories: security!

Due to the nature of the high-value product, a jeweller on a suburban high street is more susceptible to burglary and robbery than a store in a large suburban shopping centre. This and other reasons are why jewellers have been attracted to locating stores in these ‘hubs’.

In the early 2000s, there was debate around whether Australia was ‘over-retailed’. According to some experts, we had too many brands, too many shops, and too many choices. As part of that debate, Jeweller wondered whether there were too many jewellers.

Putting aside the question of ‘how many is too many’ and who should decide the correct number, a 2003 study was undertaken to measure the number of jewellery stores in all the major shopping centres of Australia’s eight capital cities.

Such an analysis had never previously been done for jewellery and, most likely, many other retail categories.

What the research found surprised many because, in part, it uncovered a formula used by landlords for nearly every shopping centre. And that formula specifically targeted jewellers!

It is fitting that - 20 years later - the matter be explored again in this State of the Industry Report (SOIR) to ascertain if there has been a change in the retail mix of the very same shopping centres.

In other words, two decades on, where and how do jewellers fit into the tenancy business model of Australia’s shopping centre behemoths?

A time before the internet

It is easy to forget, or at least overlook, that there was a time when we existed without the Internet. It was a time when deciding which product or brand to buy involved actually going shopping.

People didn’t ‘research’ something; they went shopping for it - the actual activity (walking and looking) was the research, unlike today in the digital age of immediacy.

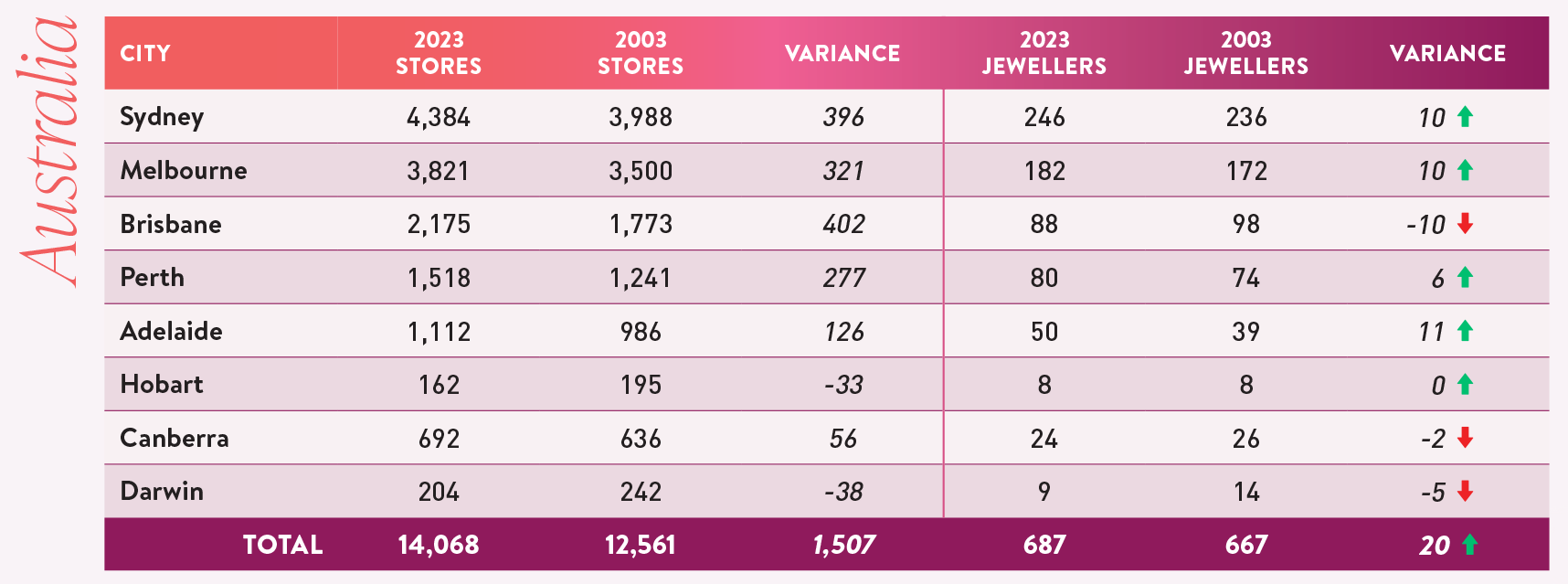

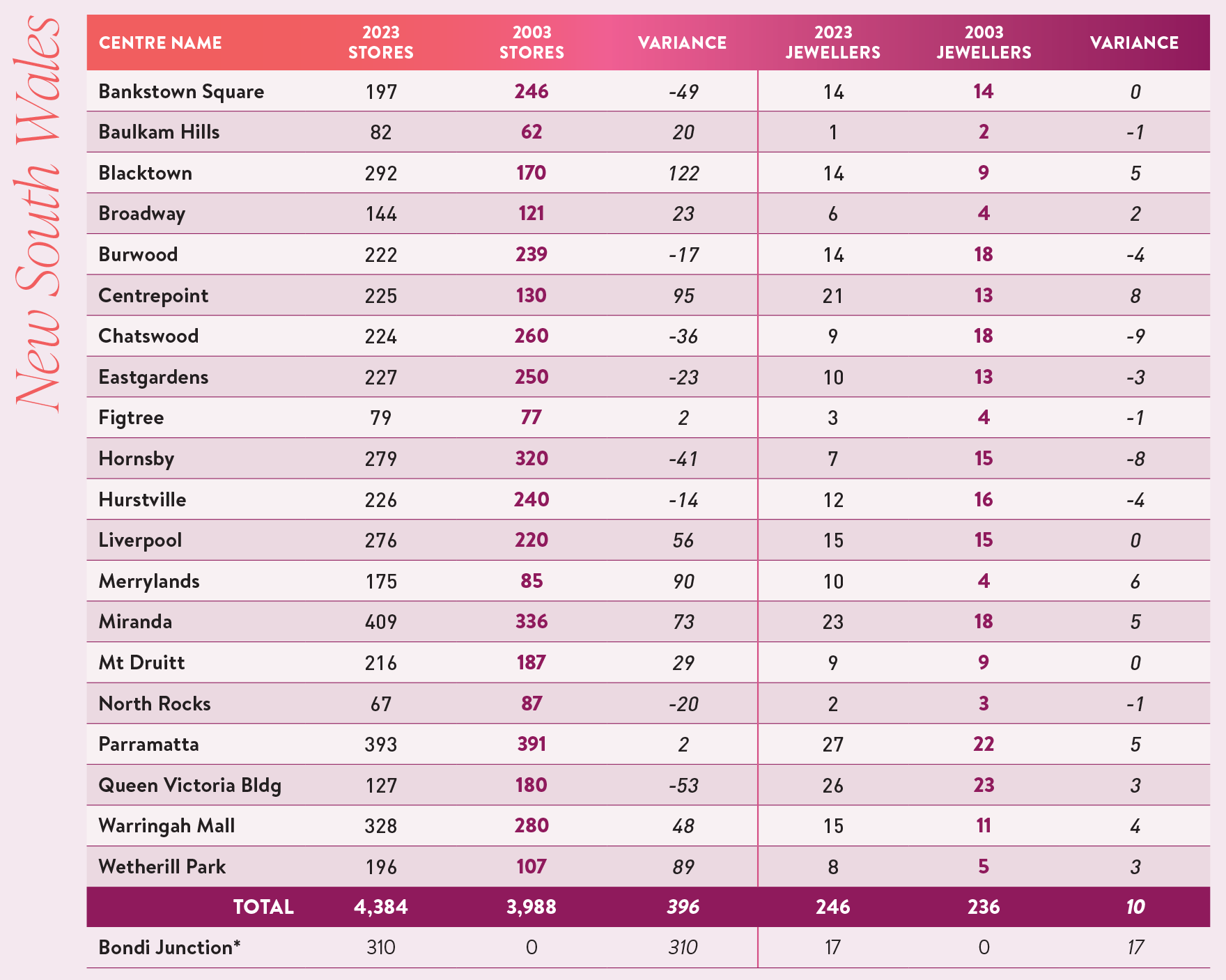

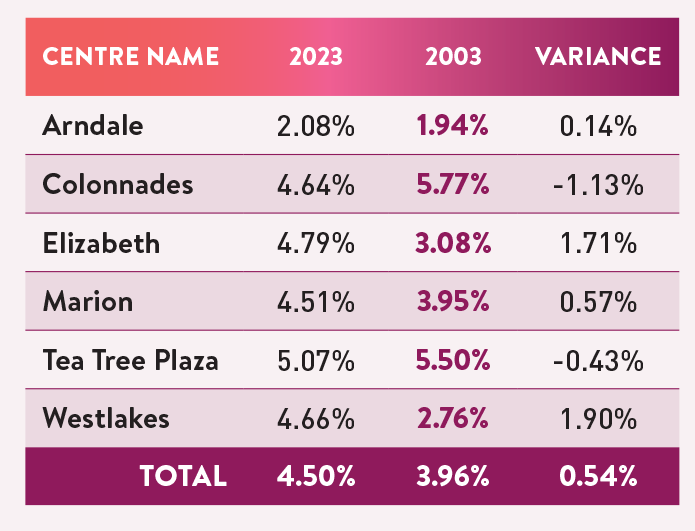

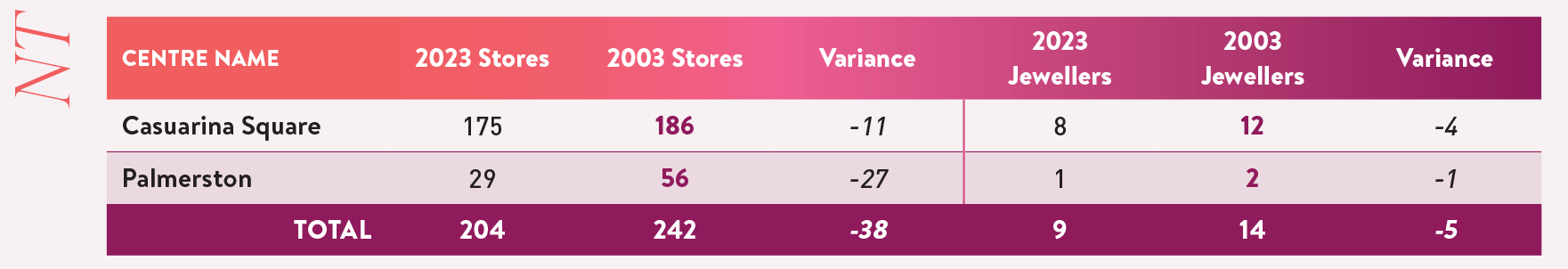

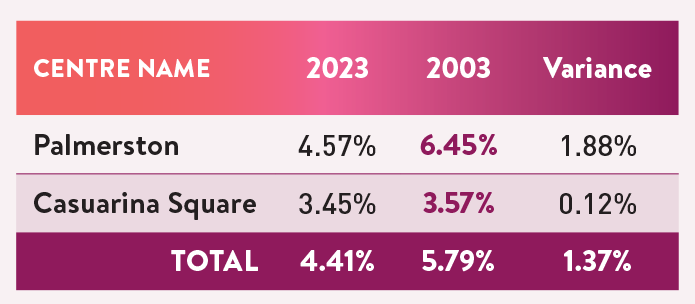

TABLE 1A: ALL CAPITAL CITIES: STORE COUNT COMPARISON 2003 TO 2023 | TABLE 1B: JEWELLERS AS A % OF TOTAL STORES |

|  |

This table compares the capital city shopping centre store counts over a 20 year period; from 2003-2023. It also compares the variation in jeweller store counts within each capital city.

| This table compares the capital city shopping centre store counts over a 20 year period; from 2003-2023. It also compares jewellery stores as a percentage of city. |

|

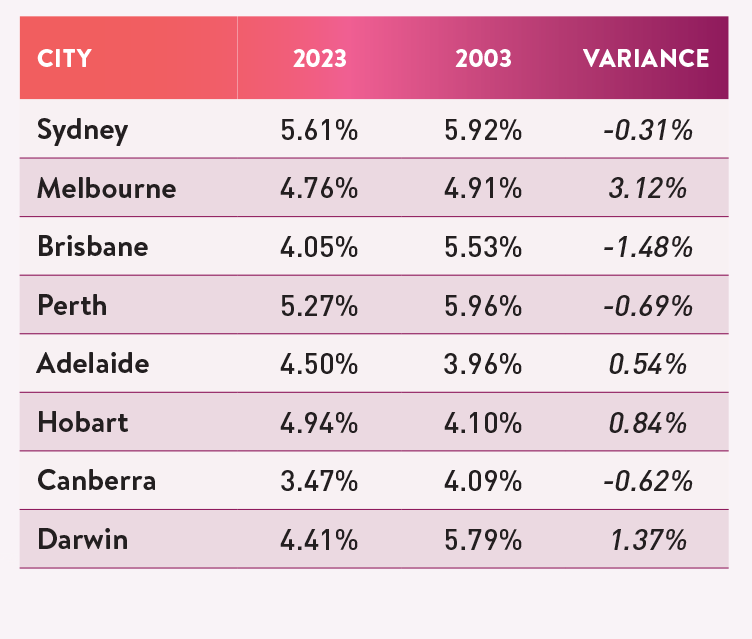

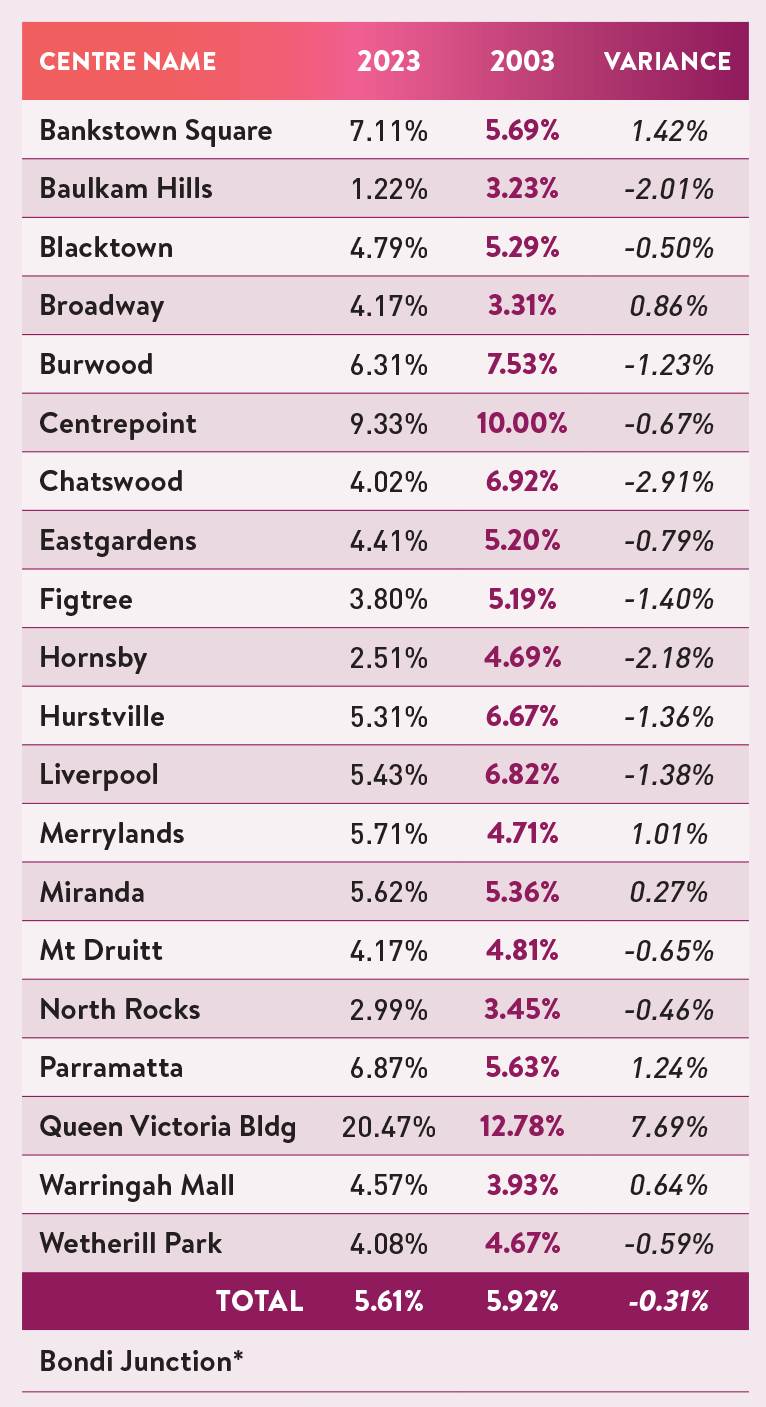

TABLE 2A: SYDNEY - STORE COUNT COMPARISON 2003 TO 2023 | 2B: JEWELLERS AS A % OF TOTAL STORES |

|  |

| * Under redevelopment in 2003 | |

And what that meant to retailers - or how they benefited - was that the store staff had a significant influence on the consumer’s pre-purchase decision(s), again, unlike today, where almost all decisions have been made via a smartphone or computer before visiting a store or shopping centre.

Think of it this way: the retail stores and staff acted as the research centres instead of the internet. In short, the shopping experience has changed dramatically!

The 2003 shopping centre investigation revealed that among the 70 major shopping centres loaded in each capital city, there were 12,561 stores. At the time, the Shopping Centre Council of Australia (SSCA) estimated that shopping centres generated approximately $84 billion in retail sales each year.

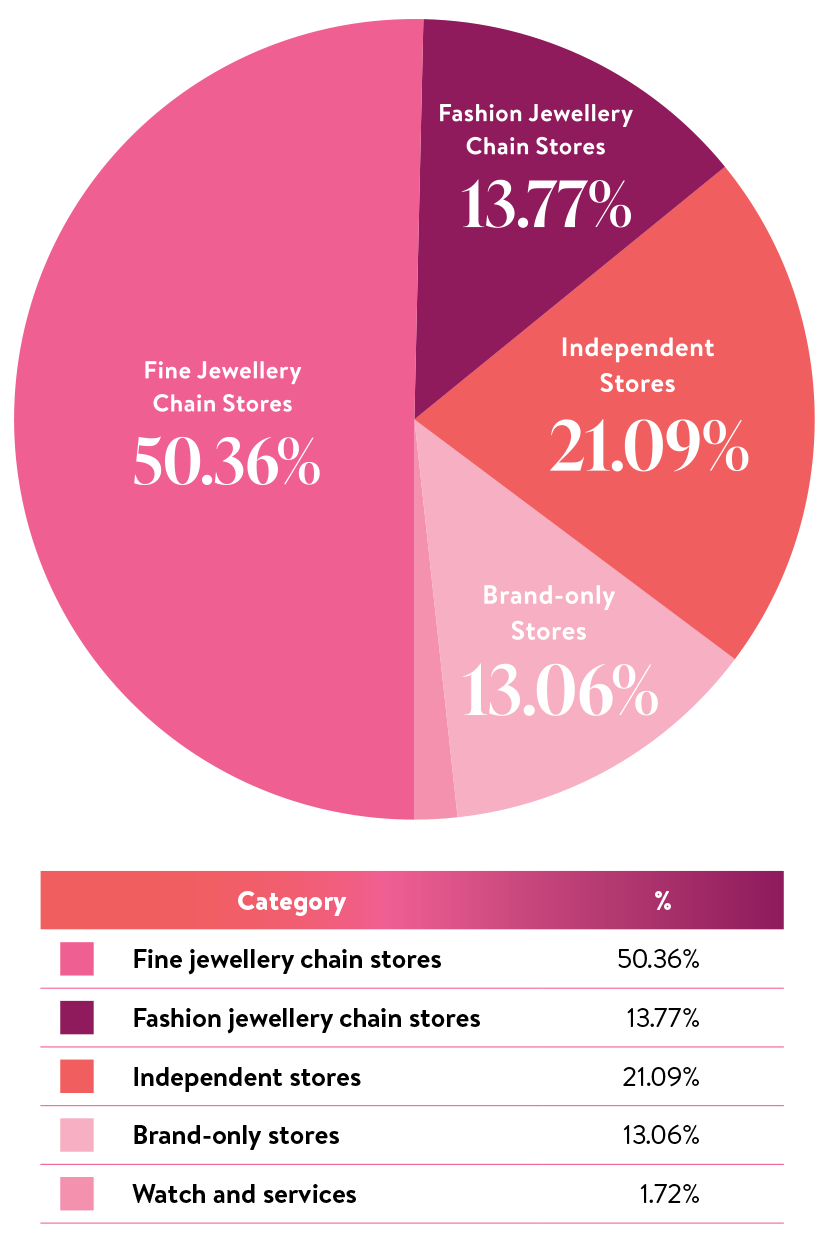

SHOPPING CENTRE STORE MIX |

|

| Chart shows the mix of jewellery stores in Australian shopping centres in 2023. |

But, here’s the thing - of the 12,561 stores, jewellery retailers accounted for 5.31 per cent.

That figure is a little ‘empty’ until you realise that jewellers accounted for plus or minus five per cent of every shopping centre surveyed.

The commonality was no coincidence!

When the same research was done in 2010, this ‘issue’ of a seemingly over-representation of jewellery stores intensified. The study found that the total store count for the same shopping centres seven years earlier had increased by 14 per cent on a like-for-like basis, and jewellery retailers accounted for 5.47 per cent of these stores – a modest rise.

The critical insight was that while jewellery accounted for just 1.4 per cent of overall retail sales in 2010, shopping centres were still dominated by jewellery retailers as more than five per cent of total stores.

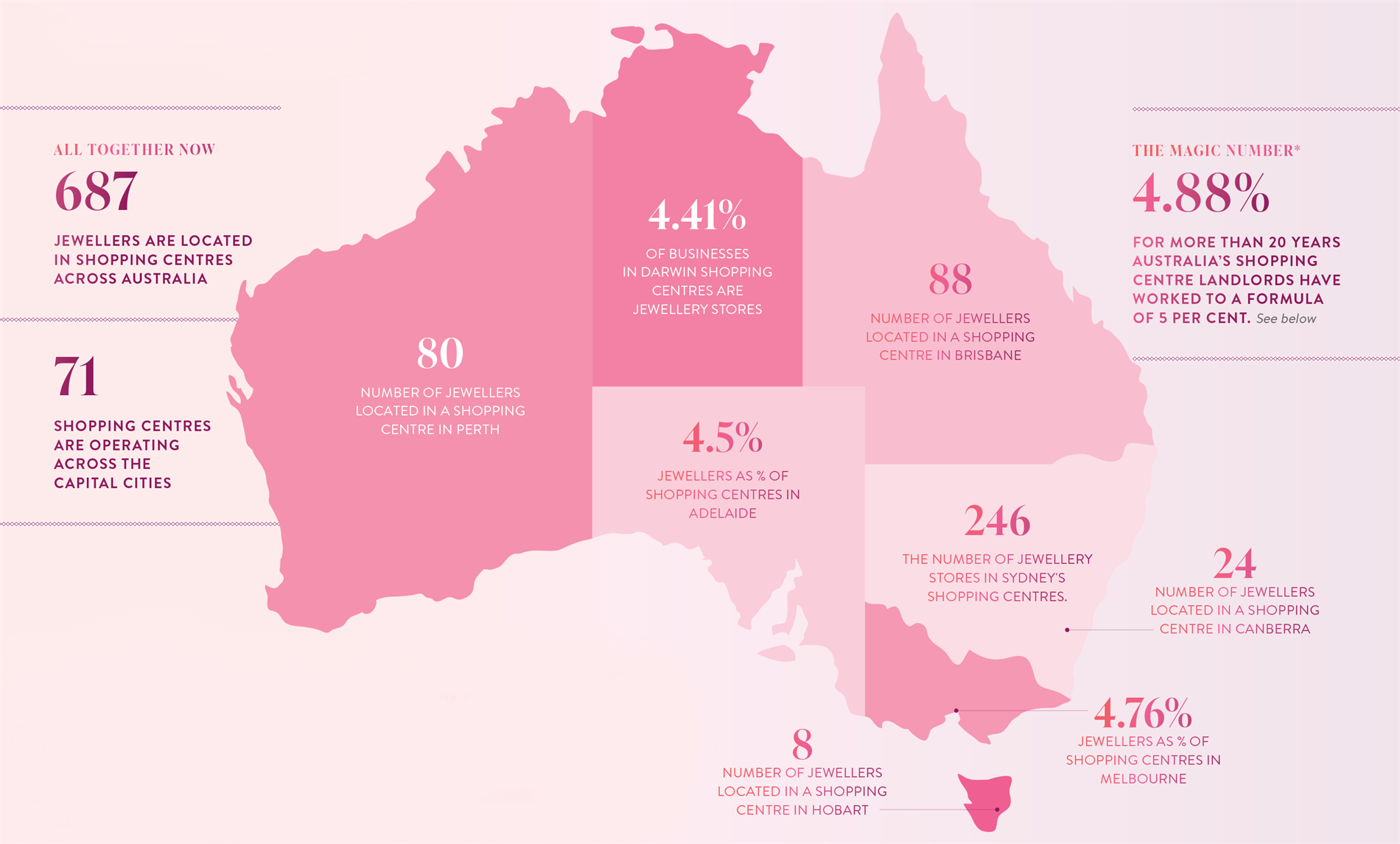

According to Jeweller’s latest research, there are 14,068 stores in shopping centres located in Australian capital cities.

This is a 10.71 per cent increase from the data in 2003; however, given that Australia’s total population has expanded by 34 per cent from 19.72 million in 2003 to 26.47 million in 2023, this would suggest that local consumers are comparatively ‘less retailed’ than they once were.

Regarding jewellery retailers, the latest data reveals that there are 687 stores in shopping centres located in capital cities – making up 4.86 per cent of the total store count.

Craig Woolford is a senior retail analyst with MST Marquee, a platform hosting research conducted by investment experts. He says the retail environment has changed considerably since Jeweller’s first report was published 20 years ago. And Woolford should know; he offered insight into the 2003 study.

“We’ve experienced somewhat limited floorspace growth in retail over the past five years specifically, and if you look forward over the next five years, we are anticipating very little growth again,” he explains.

“So while Australia still has plenty of retail floor space available, we are also seeing decent population growth, which has resulted in an ‘evening out’ of what you might consider the balance between consumers and retailers.”

This refers to the issue of ‘over-retailed’ or an overabundance of choice.

He adds: “What we’re also seeing is that while there is still plenty of retail floor space, the areas where retailers most want to position themselves – where shoppers want to go, and where sales are at their best – are in very high demand.”

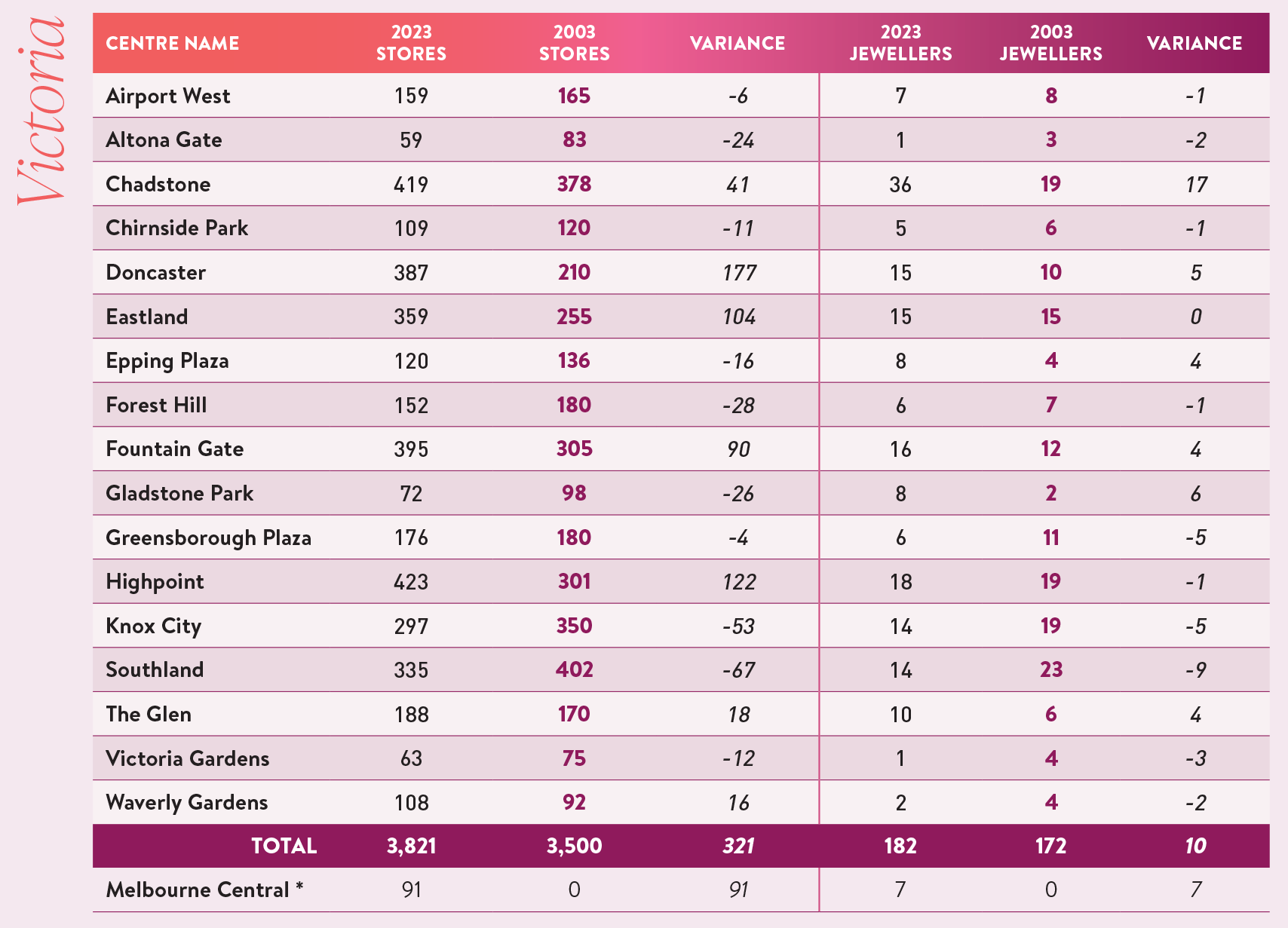

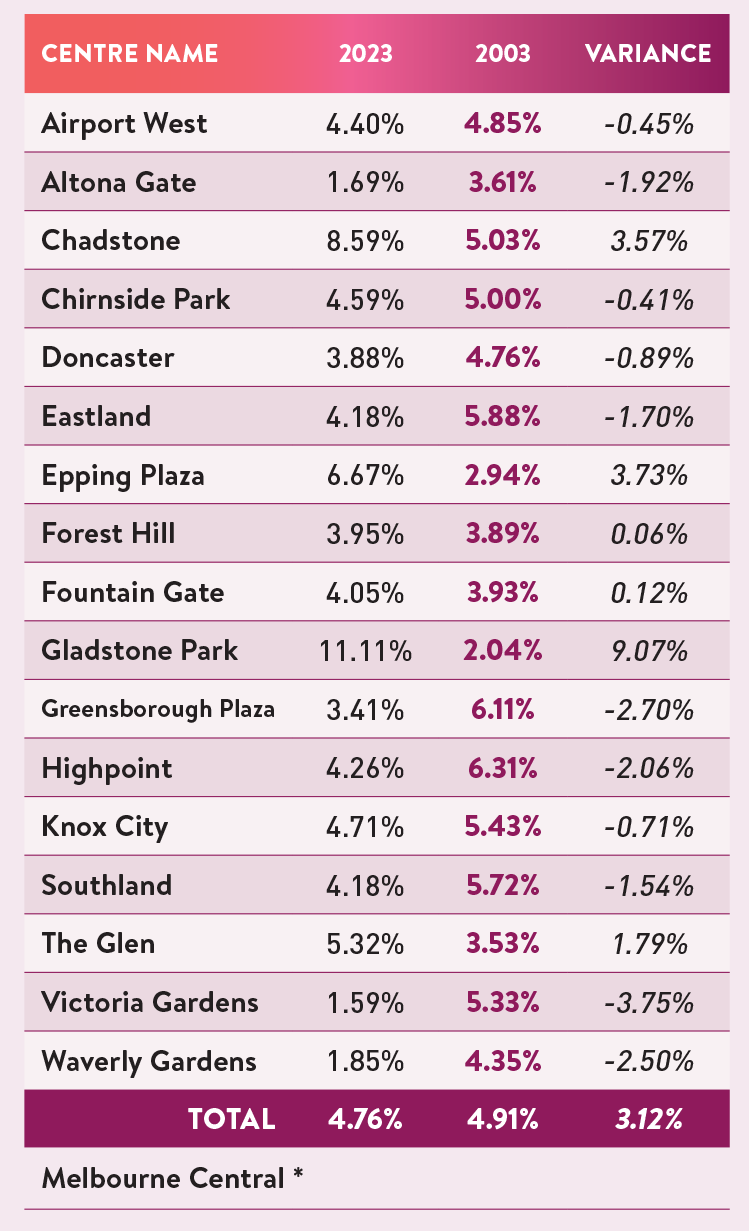

TABLE 3A: MELBOURNE - STORE COUNT COMPARISON 2003 TO 2023 | 3B: JEWELLERS AS A % OF TOTAL STORES |

|  |

| » IMPORTANT: The various tables here and on subsequent pages, show each major shopping centre in each of capital city and compares total store counts over a 20 year period; from 2003-2023. It also compares jewellery stores as a percentage of each shopping centre. As you will note, the data demonstrates the continuation of a formula first identified in 2003, where the average percentage of jewellery stores in each shopping centre is always five per cent of the total store counts, give or take one percent. |

Picture of today

Sydney and Melbourne have seen a considerable rise in shopping centre store counts in the past two decades, increasing by nine per cent and eight per cent, respectively.

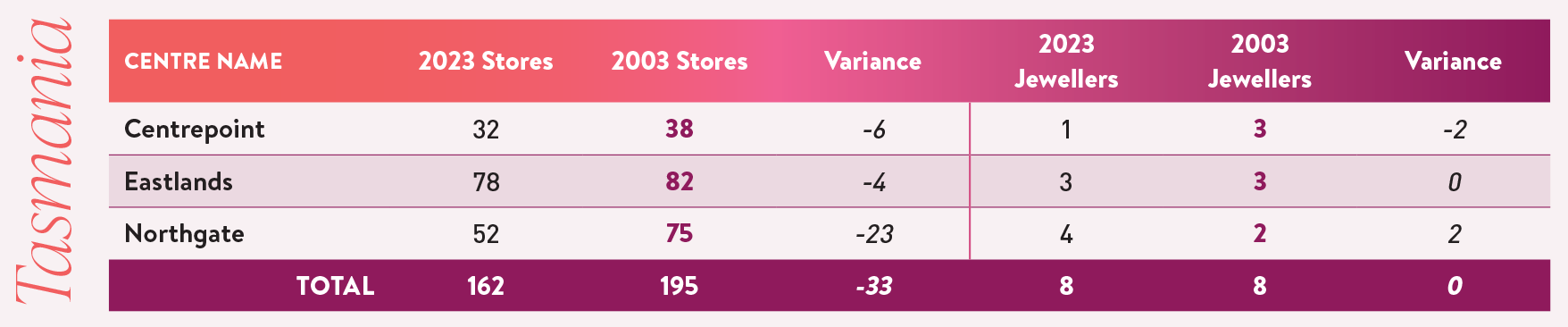

These two cities are also similar regarding jewellery retailers as a percentage of overall stores in shopping centres, with Sydney sitting at 5.61 per cent and Melbourne at 4.76 per cent.

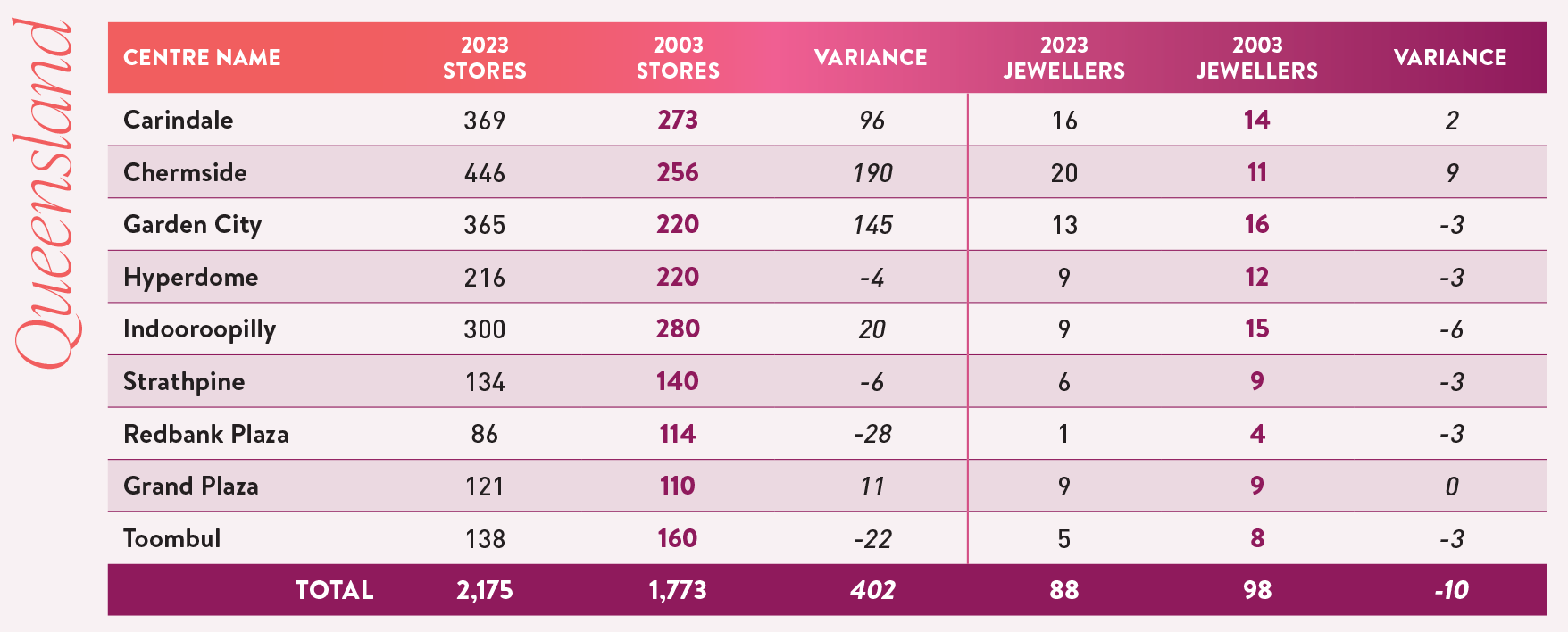

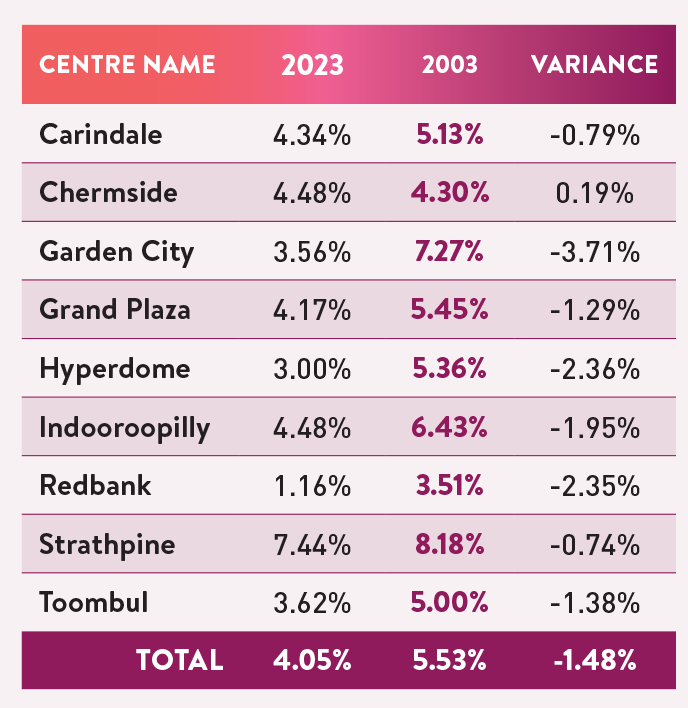

The total store count in Brisbane has increased by 18.4 per cent; however, Brisbane went against the trend. The number of jewellers declined by more than 11.36 per cent, in line with a significant decline in Queensland’s number of independent jewellers during the same period.

Jewellers represent just 4.05 per cent of stores in Brisbane’s shopping centres.

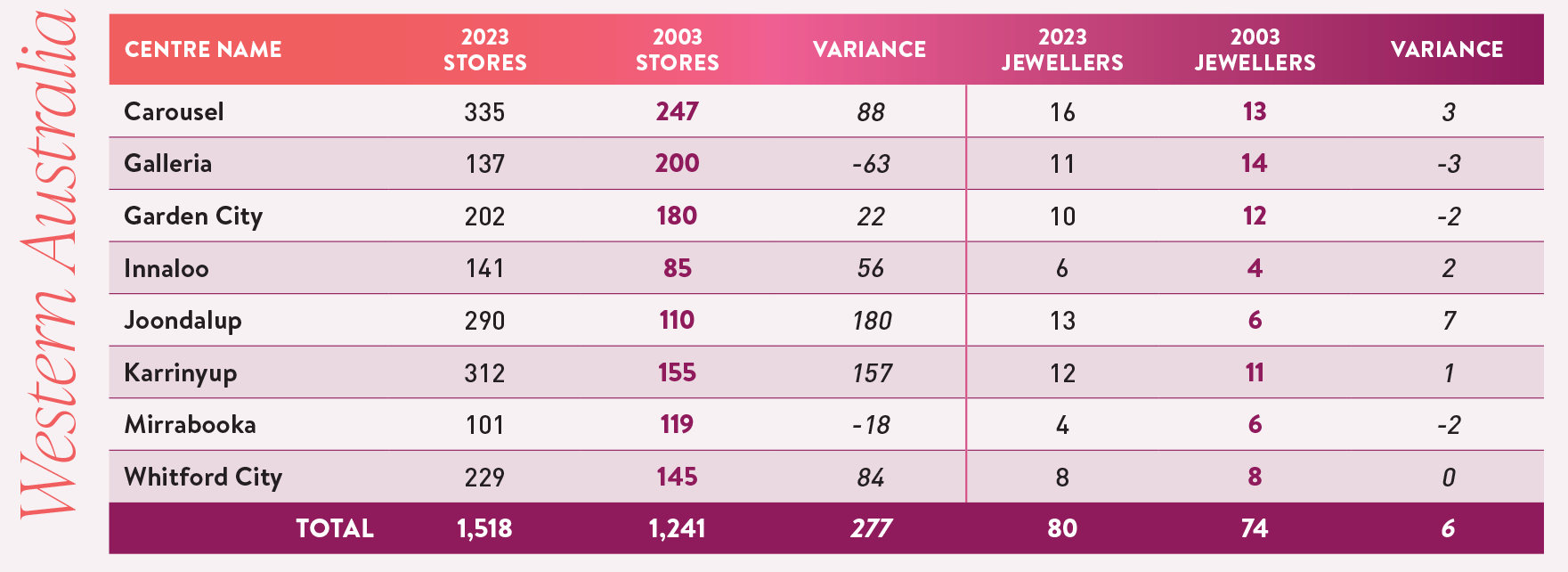

Perth has seen a similar expansion of overall stores as Brisbane, increasing by 22.7 per cent; however, the number of jewellers is closer to that of Sydney and Melbourne at 4.86 per cent. Perth’s store count expansion has been the largest in Australia over the past two decades (18.25 per cent), while Hobart has declined the most, dropping by 20.37 per cent.

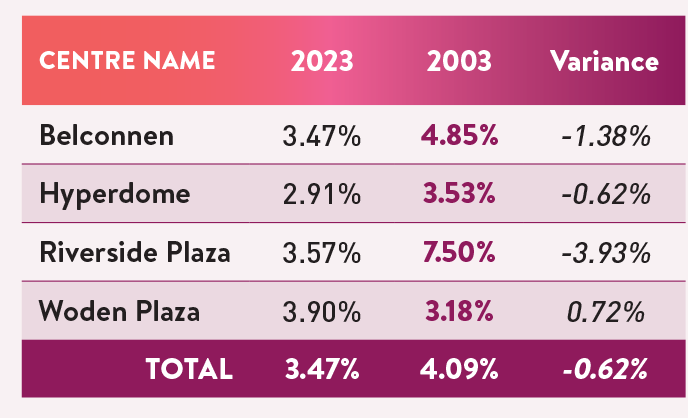

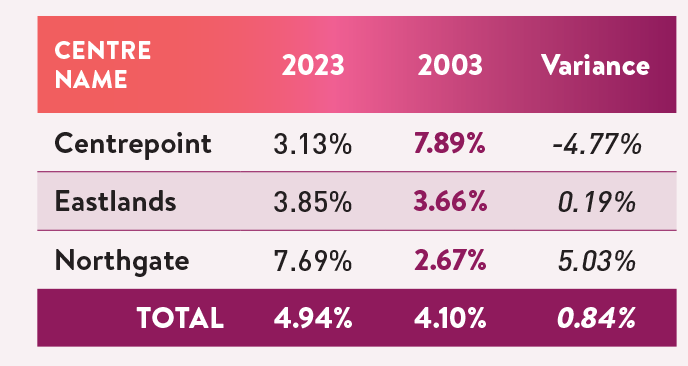

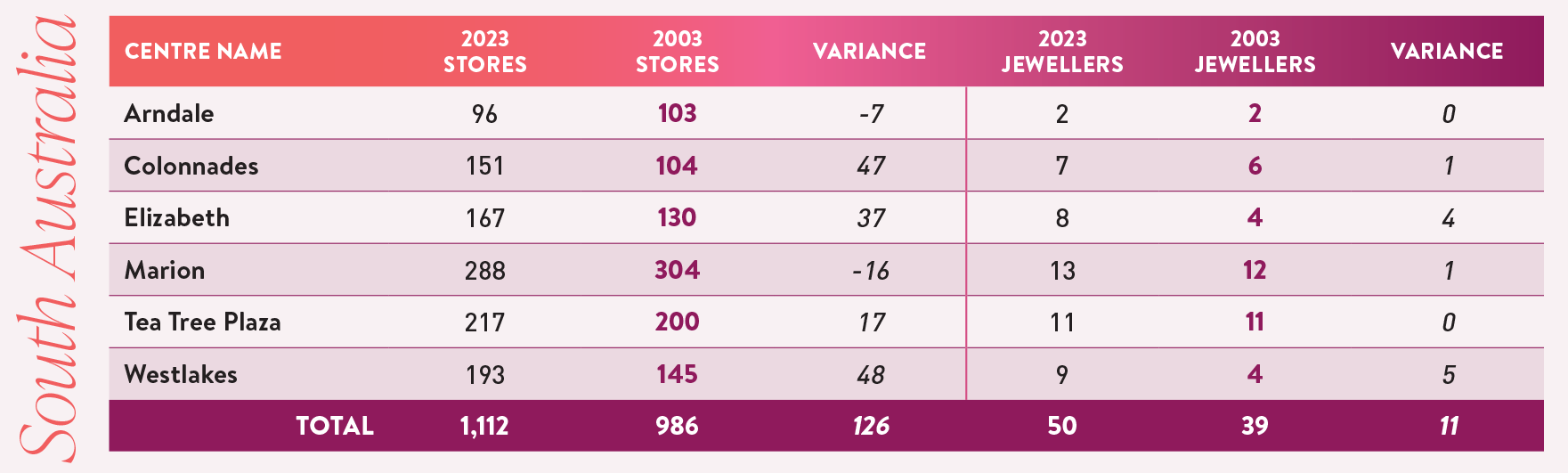

Interestingly, the mix in Tasmania remains in line with other major cities, with jewellers still making up 4.94 per cent of stores.

As the table indicates, the landlords maintain a formula of around five per cent two decades later.

Eloise Zoppos is a research and engagement director with Australian Consumer and Retail Studies, based at the Monash Business School in Melbourne. She says optimising floor space is akin to walking a tightrope for shopping centres.

“It’s crucial that shopping centres get their tenancy mix right for the success of their retailers, but also for the experience of their customers,” she tells Jeweller.

National Retail Association director Rob Godwin echoed this sentiment, suggesting that the ‘secret to success’ for retailers is to embrace change – or risk being left behind.

“The retail landscape is ever evolving and ever-growing. Customers have access to more retail options than ever before,” he said.

“Increased competition means retail businesses are continuously finding new innovative ways to cater to the customer.”

In recent years, priorities have been shifted for landlords; since the pandemic, traffic at shopping centres has decreased; however, sales remain above pre-COVID levels.

This has been attributed to consumers performing more research before shopping – meaning they enter shopping centres with a specific product in mind rather than merely browsing.

In response to this change in consumer behaviour and other factors, landlords are prioritising ‘time-consuming’ tenants that offer products and services that can’t easily be found online.

“All shopping centres want traffic. They want consumers to spend time in the centre, and the best shopping centres are experts in making this happen with the tenancy mix. We’ve seen the rise of things like ‘food precincts’ with cafes and restaurants rather than mere food courts as an example,” Woolford explains.

“Many shopping centres have reimagined the cinema precinct, changing how it looks and adding restaurants nearby to make it more of a destination for consumers. Similarly, we’ve also seen a growth in health and beauty services at shopping centres, which are a form of retail that can’t be purchased online.”

He continues: “Shopping centres have done well to reposition the floor space in a way that encourages consumers to spend more time in the centre.”

TABLE 4A: BRISBANE - STORE COUNT COMPARISON 2003 TO 2023 | 104B: JEWELLERS AS A % OF TOTAL STORES |

|  |

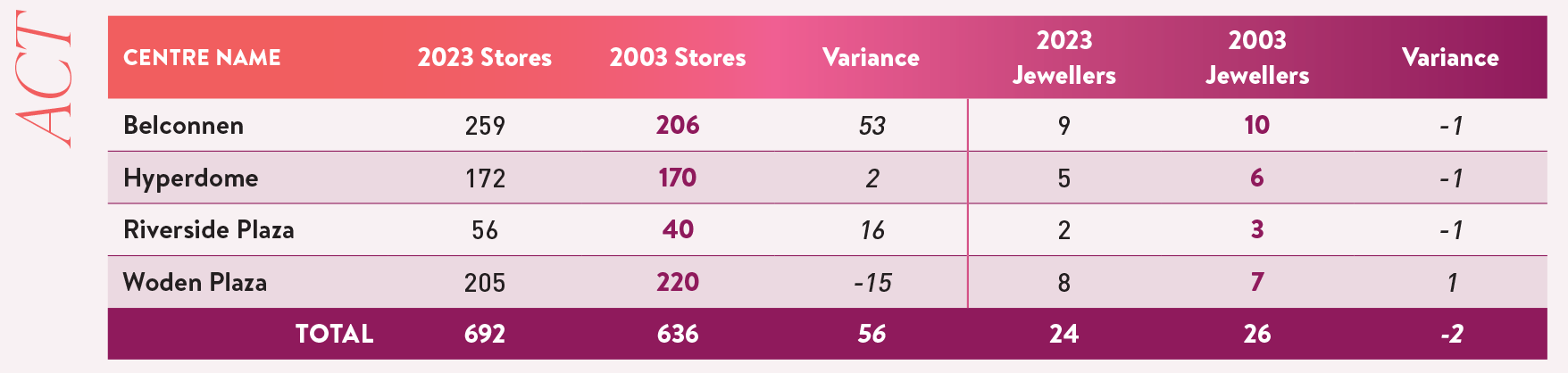

TABLE 5A: CANBERRA - STORE COUNT COMPARISON 2003 TO 2023 | 5B: JEWELLERS AS A % OF TOTAL STORES |

|  |

TABLE 6A: HOBART - STORE COUNT COMPARISON 2003 TO 2023 | 6B: JEWELLERS AS A % OF TOTAL STORES |

|  |

Are Australians over-retailed?

The original 2003 study sought insight into two questions: Do we have too many brands and retailers? Are there too many jewellers in shopping centres?

It’s a difficult question to answer – determining an appropriate benchmark for the balance between retailers and consumers is challenging.

The responses to this question at the time were mixed. Brian Sweeney, chairman of Sweeney Research, firmly asserted that Australia is ‘over-retailed’.

He suggested that in many retail categories – cars, for example – Australians could choose from almost every car brand in the world. This is not the case in other countries.

Stan Moore, chief executive of the Australian Retailers Association, disagreed that Australians had too much choice. He pointed to consistently positive retail turnover, indicating that the local market was healthy and balanced.

Alan Treadgold, director of Retail Research and Consulting, agreed with Moore and suggested the question was too broad to be answered concisely.

Brand saturation differs from category to category – for example, Australia may have a wide variety of car dealers but limited access to motorcycles.

When asked about this topic 20 years later, Zoppos presented a different perspective.

“What’s also important when thinking about whether Australia is over-retailed or not is the mix within categories and not just the number of brands or stores, with price point being one example,” she says.

“Thinking about it from the customer point of view, they may be attracted to a centre with several stores within the category for browsing and comparison purposes.”

While accurate, raw figures about store counts today can be deceptive.

The digital age means there is no such thing as a country being ‘over-retailed’ given that internet shopping and e-commerce allow anything and everything to be available at any time.

With that said, jewellers have remained a crucial ‘cog in the machine’ for shopping centres despite evolving consumer behaviour.

As mentioned, as a percentage of total stores at shopping centres, jewellers have increased by 3.68 per cent in the past two decades.

At the more affordable end of the jewellery market, impulse purchasing is crucial, and the higher level of foot traffic in shopping centres offers a chance for retailers to capitalise.

Woolford says that while sales productivity for other retail categories has changed recently, jewellery has remained consistent.

Simply put, sales productivity is about maximising output – transactions, revenue, or customer interactions – while minimising input, namely time and resources.

In other words, it's the art of doing more with less but doing it smarter. Sales per square foot/metre is also a component of sales productivity.

“Jewellery has a very high transaction value; retailers are selling a mid-market or expensive product, which means more sales per square metre. Sales productivity is very good for jewellers compared to the average shopping centre tenant,” he explains.

“So for the tenant and the landlord, this is a mutually beneficial arrangement based on what the shopping centre can offer and this sales productivity.”

By comparison, Woodford explains that sales productivity at shopping centres for fashion and apparel categories has declined in recent years, mainly due to the competition posed by major retailers - anchor tenants - such as Kmart, Target, and, to a lesser extent, Myers.

For example, Kmart has expanded heavily into clothing and homewares, undermining specialty retailers offering similar products at shopping centres.

Put another way, landlords use anchor tenants to attract shoppers to the centre, making it more attractive for specialist retailers to take leases; however, as the major retailers have changed and expanded their focus, they are increasingly competing with specialist retailers.

However, jewellers have been sheltered from these kinds of threats because of the ‘luxury’ nature of the product.

“We haven’t seen retail categories like jewellery encroached by larger format retailers, which is an important observation [from the current data],” Woolford explains.

“If you consider Kmart as an example, they’ve expanded their offering with low-end and effective fashion and homeware products, which takes away volume for the specialty retailers.

“There’s no equivalent disrupting the jewellery category as we’ve seen in the fashion and, to a lesser degree, footwear categories.”

Godwin says that whether the threat is e-commerce or larger format retailers, the focus for retailers should be on flexibility and innovation.

“Given that retailers are no longer isolated and have to exist in a global market, they have to be more agile. Possibly, having to look wider for newer customers,” he explains.

“The flat year-on-year sales in 2023 is proof that interest rates have had their intended effect. Retailers have to find new markets to make up for customers they lost during these tight economic conditions.”

TABLE 7A: PERTH - STORE COUNT COMPARISON 2003 TO 2023 | 7B: JEWELLERS AS A % OF TOTAL STORES |

|  |

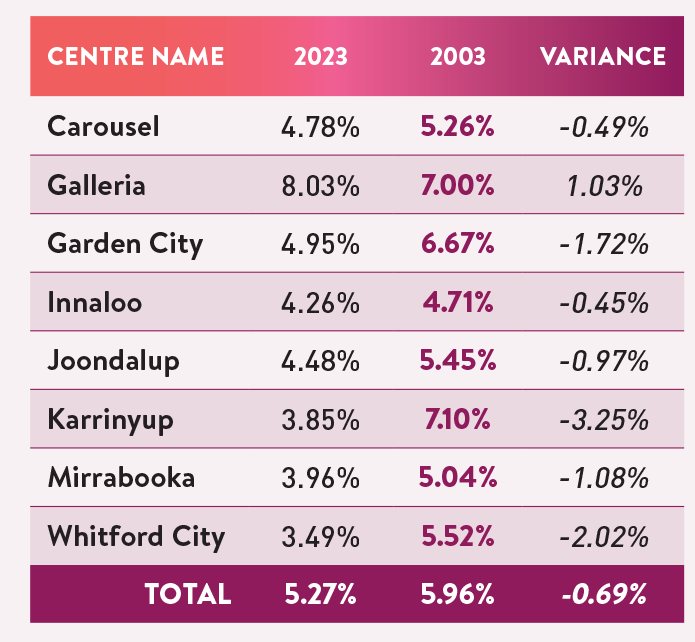

TABLE 8A: ADELAIDE - STORE COUNT COMPARISON 2003 TO 2023 | 8B: JEWELLERS AS A % OF TOTAL STORES |

|  |

TABLE 9A: DARWIN - STORE COUNT COMPARISON 2003 TO 2023 | 9B: JEWELLERS AS A % OF TOTAL STORES |

|  |

Facts and figures

While sales at shopping centres remain healthy, there are other indications that the future of these retail hubs is still being determined.

Approximately $2.5 billion worth of shopping centres in Australia have been offered for sale over the past 12 months and have yet to find a buyer.

PAR Group is a research agency that specialises in commercial property. Director Rob Ellis told The Australian Financial Review that prospective buyers are apprehensive about major acquisitions due to fears that shopping centres are overvalued.

“There just aren’t any shopping centre deals. The whole thing has dried up from a mismatch of expectations between sellers and buyers. Last year was weak as regards to sales. This year has been even weaker,” he said.

Ellis said the bulk of retail transaction activity continues to be smaller, lower-yielding retail outlets.

These smaller shopping centres often include supermarkets and have continued to sell due to their low risk and the consistent demand for grocery shopping.

The value of shopping centres sold has decreased in the past two years, falling 11.1 per cent in 12 months to $4,554 per square metre.

With that said a recent Shopping Centre News (SCN) report painted a much more optimistic picture.

The report includes a ranking of 91 shopping centres, of which 85 per cent increased their annual turnover. These centres account for an annual $54 billion in retail sales.

Michael Lloyd, the publisher of SCN, told The Sydney Morning Herald that Australian shopping centres are global pioneers in management, development and marketing.

“The figures are testimony to the professionalism and expertise of those developing and managing these centres,” Lloyd said.

“It’s not widely known outside shopping centre circles, but the Australian shopping centre industry is the world leader, and not by a short head either, but by several lengths.”

According to the report, nine of Australia’s ten biggest shopping centres had more than $1 billion in sales in 2022. Melbourne’s Chadstone shopping centre holds the largest annual turnover with $2.7 billion in sales, a 16.2 per cent increase from 2020.

Three new shopping centres have passed the $1 billion benchmark - Pacific Fair (Gold Coast), Westfield Miranda (Sydney), and Westfield Carindale (Brisbane).

2024 STATE OF THE INDUSTRY REPORT: SHOPPING CENTRES |

|

One conclusive change

While the current research indicates little or no change in the overall formula of jewellery stores constituting around five per cent of all stores in Australia’s capital cities shopping centres, the data hides one significant change.

And interestingly, the changes relate to two other parts of this 2020 SOIR - the decline in independent jewellery stores since 2010 and the increase in chain stores and the rise of brand-only stores.

Whereas in 2003, a list of jewellery stores in each centre would have included many small, family-run jewellery businesses, 20 years later, most have vacated the shopping centres. This could be because of retirement, leases ending or as a result of the pandemic; however, there is no doubt that it is also because of tenancy costs.

Independent jewellers are less likely to be able to accommodate the lease and fit-out expenses of the capital city centres - regional and rural centres can be different - and have been ‘pushed out’ by the chains. Further, as the current research indicates, there has been a large increase in the number of brand-only stores, including some very high-profile international brands such as Tiffany & Co, Van Cleef & Arpels, Piaget and so on.

One only needs to look at the jewellery and watch stores at Chadstone in Melbourne or Centrepoint in Sydney to understand that a traditional ‘family jeweller’ would have difficulty competing with international brands/conglomerates.

Two decades later, this raw data does not highlight the loss or demise of the independent jewellers in Australia’s capital city shopping centres.

STATE OF THE INDUSTRY REPORT

Published dec 2023 - jan 2024

|  |  |

A Snapshot of the

Australian jewellery industry

| To better understand the findings of the State of the Industry Report, it's important to be aware of the changes to the industry and how they affect the methodology. |

| Independent Jewellery Stores:

How many are there in Australia?The results are in and you will be surprised.

How has the retail jewellery market fared over the past decade? How does it compare to other areas of the jewellery industry? |

| Jewellery Buying Groups: The ups and downs of this vital sectorThe nature of buying groups has changed significantly in the past decade and there's an important question to be answered.

Can Australia support four buying groups? |

|

|  |  |

Jewellery Chains:

Stronger and stronger... for some!| The fine jewellery chains have performed well over the past decade; however, consolidation could be on the horizon as the 'big fish' look for new customers via retail brand differentiation. |

| Fashion Jewellery Chains:

Examining explosive collapsesThe past 10 years have been a rollercoaster ride for fashion jewellery chains, defined by rapid expansions and dramatic collapses.

That said, the carnage continues in 2024. Is anyone safe? |

| Brand-Only Watch & Jewellery Stores: Is the sky the limit?

| The most significant change over the past decade has been the expansion of the big international watch and jewellery brands as they take control of their public perception via a vertical market model. |

|

|  |  |

Births, Deaths & Marriages:

See you on the other side!

| No market is immune to change and no one escapes death. It’s time to reflect on the 'comings and goings' of the Australian jewellery industry over the past 13 years. |

| Shopping Centre Conflict:

Haven't you heard? We're at war!

| Australia’s shopping centres are a towering figure in the retail sector and fine and fashion jewellery stores have played an integral part in their speciality store 'mix'. |

| Jewellers Association of Australia:

Where does the JAA go from here?

| It's been a brutal decade for the Jewellers Association of Australia and much of the damage has been self-inflicted. Worse, the JAA's missteps don't seem to end. |

|

|  |  |

Jewellers Association of Australia:

Does it represent the industry? | As membership continues to fall, the JAA is increasingly seen as a club of like-minded people rather than a peak body. |

| Jewellers Have Their Say: Prepared to be surprised and intrigued! | What do jewellers say about the past, present, and the future? A survey of retailers and suppliers revealed fascinating results. |

| Crystal Ball 2030: Bold predictions for the future of retail| Change is inevitable; however, progress is optional. How can your business benefit from upcoming changes in the jewellery industry? |

|

|  |  |

Provenance or Proof of Origin: Does anyone seriously care? | Provenance or proof of origin is a hot topic. Conventional wisdom says it's an important issue, but in this digital era it's also important to challenge tradition. |

| You’ll never understand the universe

if you only study one planet | More often than not, the questions are complicated, but the answers are simple. Publisher ANGELA HAN reflects on the creation of the State of the Industry Report. |

| Listen to what is not said,

for there, the true story lies | Editor SAMUEL ORD explains some of the behind-the-scenes work that went into this State of the Industry Report and discusses expectations and reality. |

|

STATE OF THE INDUSTRY REPORT - ADDENDUMS

SINCE JANUARY 2024

|  |  |

Questions of legacy and accomplishment for the JAA| The structure of the JAA is unique, which causes complexity in measuring its success. To look to the future, one must recognise the success and failures of the past. |

| Why is Queensland so different? Well, the answer is: Because it is!| Over the past decade, Queensland's number of jewellery stores decreased dramatically more than any other state. Why? The answers are intriguing. |

| Grey areas: Jewellers operating without a retail storefrontAs trends emerged and consumer shopping habits changed, so too has retailing.

The COVID pandemic probably hastened the move towards specialist jewellers, those that do not require a storefront. |

|

| |  | |

| | WHAT! You are telling me that your business doesn't have a website?| If you had to guess, how many of Australia's independent jewellery retailers don't have a website? Would you say 100, 200, or even 300? How about 400, 500, or 600? |

| |

Hover over eMag and click cloud to download eMag PDF

PREVIOUS ISSUES